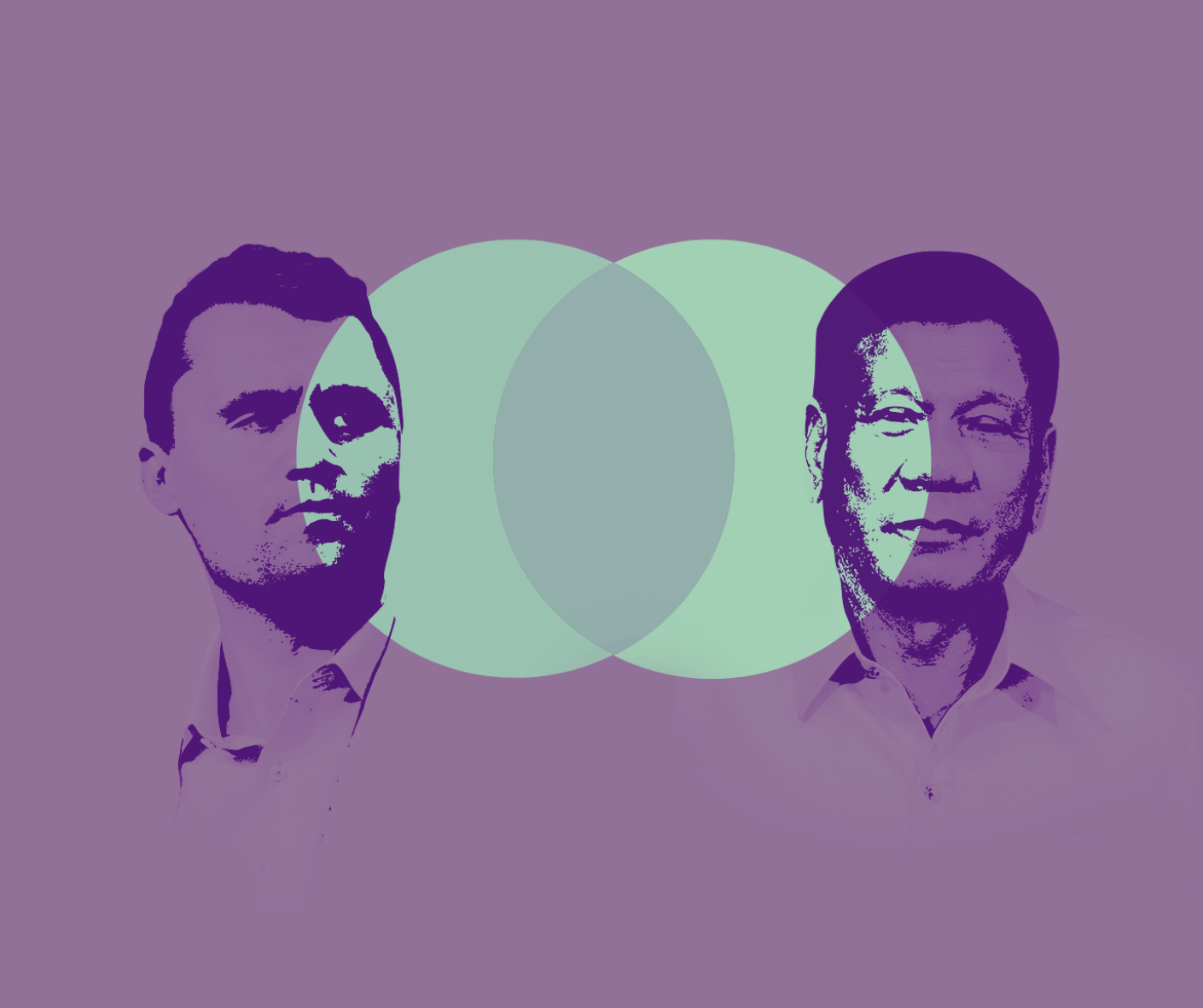

A Filipino American’s take on discriminatory policies and their connection to indiscriminate horrors.

On September 10, 2025, a man who advocated for the widespread ownership of guns died because of a man who had one.

I was crouched on the floor of a shoe store in Texas when I found out about this; surrounded by rows of brightly colored socks my 3-year-old was eagerly sorting through. My smartwatch buzzed against my wrist. I glanced down, expecting the usual reminder or text, but instead, the screen glowed with something else entirely: a breaking news alert announcing that Charlie Kirk had been shot dead at Utah Valley University.

My initial reaction was disbelief; surely it had to be a joke. I furiously searched Reddit, and my feed was flooded with half-formed threads, speculation, and frantic comments piling up by the second. The absurdity wasn’t lost on me; I was negotiating Hello Kitty and Disney Princess socks with my toddler while the world outside seemed to be losing its footing.

And, it didn’t stop there. Later that day, I learned of another shooting in Colorado, where a high school student opened fire inside his school, injuring two classmates.

Though the circumstances were different, the fact that these shootings happened within hours of each other underscored how routine gun violence has become on American soil—and that is part of Kirk’s legacy.

Born Charles James Kirk on October 14, 1993, the man was the founder of the conservative youth organization Turning Point USA. A supposedly devout Christian, Kirk became a defining figure in the new wave of right-wing activism, building a career on his ability to turn grievance into spectacle.

Since launching his group in 2012, Kirk cultivated the image of a youthful insurgent railing against what he cast as liberal orthodoxy on college campuses, framing himself as both provocateur and “truth-teller.” But his influence rested less on policy expertise than on provocation itself. He painted feminism as corrosive to Christian values; he compared abortion to the Holocaust, he warned of demographic shifts that supposedly imperil American identity, and dismissed queer rights as cultural decay. His daily show thrived on these tensions, reframing headlines as proof of a country under siege—a performance that earned him both a fervent following and equally widespread criticism.

Gun rights were among the topics Kirk touched upon. His defense of the Second Amendment took on a near-theological quality. For him, it wasn’t just a constitutional safeguard but a cultural talisman—proof that individual liberty must outweigh collective safety.

Of course, scientific evidence warns against this. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—a federal public health agency that works to protect Americans from diseases, health threats, and outbreaks through research, surveillance, and prevention programs—firearms continue to be one of the leading causes of death among young people in America. The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health—a world-leading institution dedicated to research, education, and policy that improve global health and prevent disease—also published a report saying the same thing. Meanwhile, the Harvard Gazette also reported this year that gun deaths have risen in the United States as state and local governments relax gun laws. Still, Kirk and his allies stood firm in their support of guns—an irony, since most of them claim that their support for abortion rests on the desire to protect life.

Once, Kirk argued that it was “worth it to have a cost of, unfortunately, some gun deaths every single year so that we can have the Second Amendment to protect our God-given rights.” And so, a sacrifice was made to the altar of this faith. Ironically, it was he who was chosen this time around.

That Wednesday, at 31 years old, while speaking to students on a campus not unlike the many scarred by school shootings in America, Kirk was fatally shot in the neck.

Those on the left called it karma; others called it justice. Those on the right called it an attack from the “violent left,” even without hard evidence. And among religious groups—mostly Christian organizations that remain dwarfed by Catholicism—they called it martyrdom. But to be dispassionate about this is to call it what it is: the death of a man caused by lenient access to guns. Those who enabled this but didn’t want such results to happen basically fucked around and found out.

As someone who came from the Philippines, I’m familiar with such eventualities. It was very apparent during the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte.

The “War on Drugs” that Became a “War on the Poor”

When he was campaigning for the highest seat in the land, Duterte didn’t spend much time clarifying how he’d elevate the Philippines.

Instead, he wielded the specter of illegal drugs before voters. It was hardly the country’s foremost security threat, but it was simple, legible, and easily vilified—a foil against which he could cast himself as a conquering hero. He promised to rid the country of illegal drugs and kill by the thousands to achieve it. And with this, he projected himself as a strong leader—the kind who could, perhaps, stamp out corruption, successfully defend the country in a territorial dispute with China, and alleviate poverty by pushing a strong agenda.

His critics warned the public about him. Various organizations—like Amnesty International—cautioned against his rhetoric and the dangers of disregarding both due process and human life. This issue was made more relevant by the fact that Duterte had long been accused of tolerating—if not employing—murderous vigilantes in Davao, where he ruled as mayor. The Davao Death Squad, they called it—also known by its acronym, DDS.

But many of his supporters didn’t listen. They even claimed the term DDS, deodorizing it by changing the meaning of the acronym to “Diehard Duterte Supporters.” To them, Duterte seemed like a worthy candidate. They weren’t turned off by his promise of violence; they presumed it would be necessary to bring about meaningful change. Many also believed that it should only be feared by the guilty and uncooperative.

This didn’t appear to be the case. Following his win, Duterte mobilized the police to create the image of an administration proactively dealing with the drug problem—and the results were bloody.

According to a report by Reuters, police officers were given monetary incentives for kills, and sources for this report—insiders within the force—stated that this became a source of moral corruption. In order to meet their quotas, some officers apparently staged crime scenes, planted guns or drugs beside bodies, and wrote reports claiming the victims had retaliated. The term nanlaban—a Filipino word for those who supposedly fought back—became a convenient alibi for murder. Meanwhile, many officers were allegedly urged to participate, fearing that if they didn’t, they’d be included in the list of drug suspects to be killed.

Because of this, Human Rights Watch reported that unlawful killings were widespread during Duterte’s presidency. Amnesty International likewise started referring to the so-called campaign as a “war on drugs”—quotation marks included—because, in its view, it was really a war against the poor. The group’s investigations found that the campaign targeted impoverished and marginalized communities, and that many killings were extrajudicial in nature. Meanwhile, major drug traffickers and suppliers remained largely untouched, exposing the selective nature of the government’s brutality.

There was also collateral damage. Among the most harrowing cases that even Duterte’s staunchest defenders struggled to justify was that of three-year-old Myca Ulpina, who died after being shot during a police raid targeting her father, Renato Dolofrina. The police insisted that Dolofrina used the child as a human shield, but Amnesty International questioned the account, noting that officers enforcing the “drug war”—emboldened by Duterte’s rhetoric and support—had repeatedly staged scenarios to legitimize killings.

This pattern was seen in the killing of 17-year-old Kian Delos Santos, whose death became a symbol of the war’s moral collapse. Police accused him of being a drug courier and claimed he fired at them while fleeing arrest, prompting them to shoot back and kill him. But CCTV footage and eyewitness accounts told a different story: plainclothes officers were seen dragging a young man—believed to be Delos Santos—toward the alley where his body was later found. Witnesses said Delos Santos was blindfolded, forced to hold a gun, told to run, and then shot dead. He was unarmed.

Those who knew Delos Santos described him generally as a good kid who had never been in trouble with authorities. Ironically, his old social media posts also showed that he was a support for Duterte and the drug war that would later claim his life.

Delos Santos’s story distilled the tragedy of Duterte’s Philippines: a nation where even the faithful could be consumed by the violence they once applauded.

Furthermore, Duterte’s term had a number of glaring shortcomings. During and after his presidency, widespread corruption in government projects was exposed left and right; some through extensive inquiry, others through public suffering, which eventually led Filipinos—including Duterte’s supporters—to once again clog the streets in protest. China also further expanded its occupation of Philippine territories while Duterte undermined his country’s rights to them. He was also openly supportive of China and its government. Further investigations into the status of illegal drugs in the Philippines revealed that his “war” didn’t achieve much success. And at the face of scrutiny, he would mock critics, threaten them with physical harm, and drop statements like “your concern is human rights; mine is human lives.”

Then came the next presidency.

By the last leg of Duterte’s term, the country was preparing to choose a new president, and the leading candidate was Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the son of a dictator constantly caught lying about his achievements and competence.

Duterte’s supporters backed him because of his insistence on continuing Duterte’s work. Their alliance was such that his daughter, Sara, who was expected to run for president, instead ran as his vice president. This happened even as warnings about Marcos’s untrustworthiness became one of the key criticisms of his character.

After the pair won, it didn’t take long for their so-called Uniteam tandem to dissolve. Sara, selected as the administration’s first education secretary, was soon put under heavy scrutiny for her questionable use of public funds. This eventually led the vice president to lash out and go on an aggressive tirade that saw her threatening the lives of the president and his allies—leading critics of both the Marcoses and the Dutertes to compare her to her father.

Then came what was seen as another betrayal of Marcos Jr. The International Criminal Court, tasked with investigating human rights violations during Rodrigo’s reign, managed to apprehend the former president—thanks in part to the cooperation of the Marcos government. He is now in The Hague, awaiting trial, while his daughter spends most of her public appearances lobbying for his release and courting public sympathy.

Meanwhile, those critical of both parties were left repeating to the public what they’ve been saying for years: “We told you so.”

In America, we say that a lot too—especially when it comes to the subject of guns.

The Discriminatory and the Indiscriminate

In the U.S., the obsession with firearms has made danger feel like Russian roulette.

I could be at the grocery store, minding my own business, and end up dead—like the victims of a recent shooting at an Austin Target just 20 minutes from my home.

What terrifies me most, though, is sending my kids to school, never knowing if they’ll walk back through the door.

About three years ago, I learned that schools across the U.S. hold active shooter drills—training children to prepare for the unthinkable. When I was a student in the Philippines, the only drills we had were for fires and earthquakes. We never once hid under desks in preparation for a gunman storming our classroom because that wasn’t a common scenario. Yet here, that trauma is normalized for American children.

Gun rights advocates—many of whom claim to be pro-life—continue to downplay the crisis. The Gun Owners of America even went so far as to say that school shootings are “rare,” despite evidence showing a steady upward trend. The statistics say otherwise.

This is one of America’s greatest dangers. Conservatives love to call themselves protectors of children; they long to have the power to control women’s bodies so they can protect fetuses, and people support them for it. Yet, these are the same people who would leave children vulnerable to preventable slaughter. Kirk was among them. And his death by gun violence, which should have been a cautionary tale against loose gun ownership, was instead twisted into something far darker.

The aftermath of his assassination was clouded in disinformation. Extremist voices flooded the public sphere with calls for vengeance. Liberals were blamed before authorities even identified the shooter as a white man from a conservative family.

On Truth Social, Donald Trump claimed that “for years, the radical left have compared wonderful Americans like [Kirk] to Nazis and the world’s worst mass murderers and criminals. This kind of rhetoric is directly responsible for the terrorism we’re seeing in the country today.”

The irony is glaring. Trump condemned “radical left” rhetoric as fueling violence—even as Kirk himself had long normalized violence as the price of liberty. He said this even as Kirk, on many occasions, attempted to undermine—if not demonize—those who aren’t like him: a white, cisgender straight Christian man.

I don’t celebrate Kirk’s assassination. I do not condone the way he died in front of his wife and children. No one deserves that trauma. But his death cannot erase the reality of his life. It’s disturbing to watch Christian nationalists rewrite his legacy, whitewashing rhetoric that caused real harm.

What’s worse is seeing Filipinos—including public figures with millions of followers—honoring him simply because he presented himself as a “man of God” and they do love to come across as such in a religious country. Many of them were the same voices who posted Bible verses while justifying violence against the poor and the abuse of minorities like the LGBTQIA+. These were also the same people who are now calling for justice and peace and all feel good ideals even though they stayed silent during far greater tragedies: from the ongoing genocide of Palestinians to the widespread corruption in the Philippines.

But was Kirk really a man of God? Do any of his proud supporters actually abide by the teachings of Christ?

I was born and raised Catholic. I went to Catholic school all the way through college (shout-out to the Pontifical and Royal University of Santo Tomas). And if I’ve learned anything, it’s this: Jesus was what people now call “woke.” He was radical. He was a leftist. He overturned tables, destabilized oppressive systems, and was crucified for sedition. He lived a life of unconditional love and empathy. And empathy was exactly what Kirk mocked as “a made-up, new age term.”

That rejection aligned with his broader ideology—emphasizing personal responsibility and individualism over collective care. It’s a mindset many Filipinos shared as they lauded Duterte and his violence. This way of thinking helped conservatives justify ignoring systemic injustice that disproportionately harms brown people, women, immigrants, and the LGBTQIA+ community.

I am part of several of those groups. As a mother, a Filipina, and an immigrant, I was a direct target of rhetoric like Kirk’s—rhetoric that many Filipinos in America and the Philippines continue to romanticize simply because he cloaked it in Christianity.

I enlisted in the U.S. Army in 2019 and became a citizen in 2020. None of that matters now, not when the Supreme Court has upheld U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) authority to racially profile Californians—a ruling that effectively legalizes discrimination. It undermines the very principles I swore to defend as a soldier.

For me, Kirk’s rhetoric wasn’t abstract. It was personal. Every time I leave the house, I carry a double fear: of random mass shootings and of being detained by ICE, regardless of my citizenship and service. The thought of being torn from my family gnaws at me daily. I can’t help but wonder—was this type of fear also felt by the Filipino poor who began to realize that they were all potential targets of Duterte’s drug war? And if I get taken, would I simply be dismissed as someone who must not have gone through the correct channels to earn my citizenship while my family suffers the effects of my abduction? If I die because of another rampaging gunman, will I simply be buried under rhetoric seeking to give people more guns?

The far right, of which Kirk was a symbol, cultivated this cruelty. His dismissal of systemic racism, rejection of white privilege as a “racist idea,” and promotion of replacement theory all reinforced indifference to brown suffering.

And it didn’t stop with race. Kirk also reinforced harmful gender norms, preaching traditional roles for women even as his wife, Erika, pursued multiple leadership positions, hosted a podcast, and worked toward a doctorate—her success made possible by the very feminism their movement derided.

Kirk’s public life was the antithesis of Christ-like values. He consistently spat on the teachings of Jesus, promoting a worldview where those who weren’t straight, white Christians were denied dignity and protection.

Now, his death is being weaponized by Trump and his allies. They frame it as proof of left-wing hostility, despite evidence that most political violence comes from the right. Critics of Trump, Kirk, and the far right are also doxxed, silenced, and even punished.

Jimmy Kimmel, for instance, said on his show Jimmy Kimmel Live! that Trump and his allies were “desperately trying to characterize this kid who murdered Charlie Kirk as anything other than one of them” and trying to “score political points from it.” In response, Trump’s allies put public pressure on the American Broadcasting Company, which was behind his show. This, in turn, led to Kimmel’s program being suspended for days.

All of this only deepens my fear that America is sliding into authoritarianism. And as a Filipino, I fear that. It’s something my people have been through.

Martial law: the darkest period of our history. Ferdinand Marcos Sr.—father of the country’s current president—justified its enactment by focusing on the supposed communist threat and civil unrest (which was really just a result of the anger inspired by the corruption in his government.)

At that time, critics of the dictatorship were tagged as rebels or communists, among others—labels that justified their vilification, imprisonment, and even murder.

Duterte didn’t enact nationwide martial law, but he certainly employed similar tactics. The most forceful of his critics were maligned as addicts, enablers, or traitors; others were hounded by trumped-up charges. Among those targeted was Rappler, the online news organization founded by Maria Ressa, who would later win the Nobel Peace Prize for her defiance.

When I watched Ressa’s recent interview with Jon Stewart, her warnings hit home. She compared Trump’s tactics to Duterte’s, noting how both use fear, anger, and hate to consolidate power. And so came her warning: “If you don’t move to protect your rights, you lose them,” she told Stewart. “And it’s so much harder to reclaim them.”

This, of course, was not just for Americans. It is for all who can empower others through their support. Many of us have misused this.

Throughout history, we’ve been approached by people who claim to value lives, and we supported them. Many of us continued our support even as it became clear that their compassion extends only to a select few.

Discrimination begins with a simple lie: that some lives are worth less than others. It slips quietly into language, law, and habit, reshaping the moral terrain until cruelty seems reasonable. Once a society accepts that certain people deserve less protection or fewer rights, it becomes easy to rationalize harm—and nearly impossible to contain it. The logic of inequality is always contagious.

We saw this when Nazism flourished, and the illusion of safety for the “privileged” dissolved in the fires of global war. We see it again in nations that speak of security while loosening the rules around those who may carry a gun. What begins as a promise of protection ends with bodies in classrooms, churches, and grocery stores. A culture that treats violence as freedom cannot tell the difference between self-defense and self-destruction.

Discrimination corrodes the very systems meant to defend us. It teaches courts to look away, police to overreach, and citizens to mistake indifference for strength. Its borders always blur; the targeted and untargeted alike fall to the same decay. The harm may begin with a few—but it never ends there. History teaches us, over and over again, that discriminatory protections always lead to indiscriminate harm.

But we have a chance to correct our mistakes.

Kirk may be gone, but many of those who share his beliefs continue to court public support. Meanwhile, come 2028, the Philippines will once again hold another presidential election, and Duterte’s daughter—a woman who, like her father, has been repeatedly linked to corruption and the penchant to disregard life—is expected to run.

Will they prevail? Or will we finally realize how important it is to stop giving guns to those who appear unqualified to wield them?