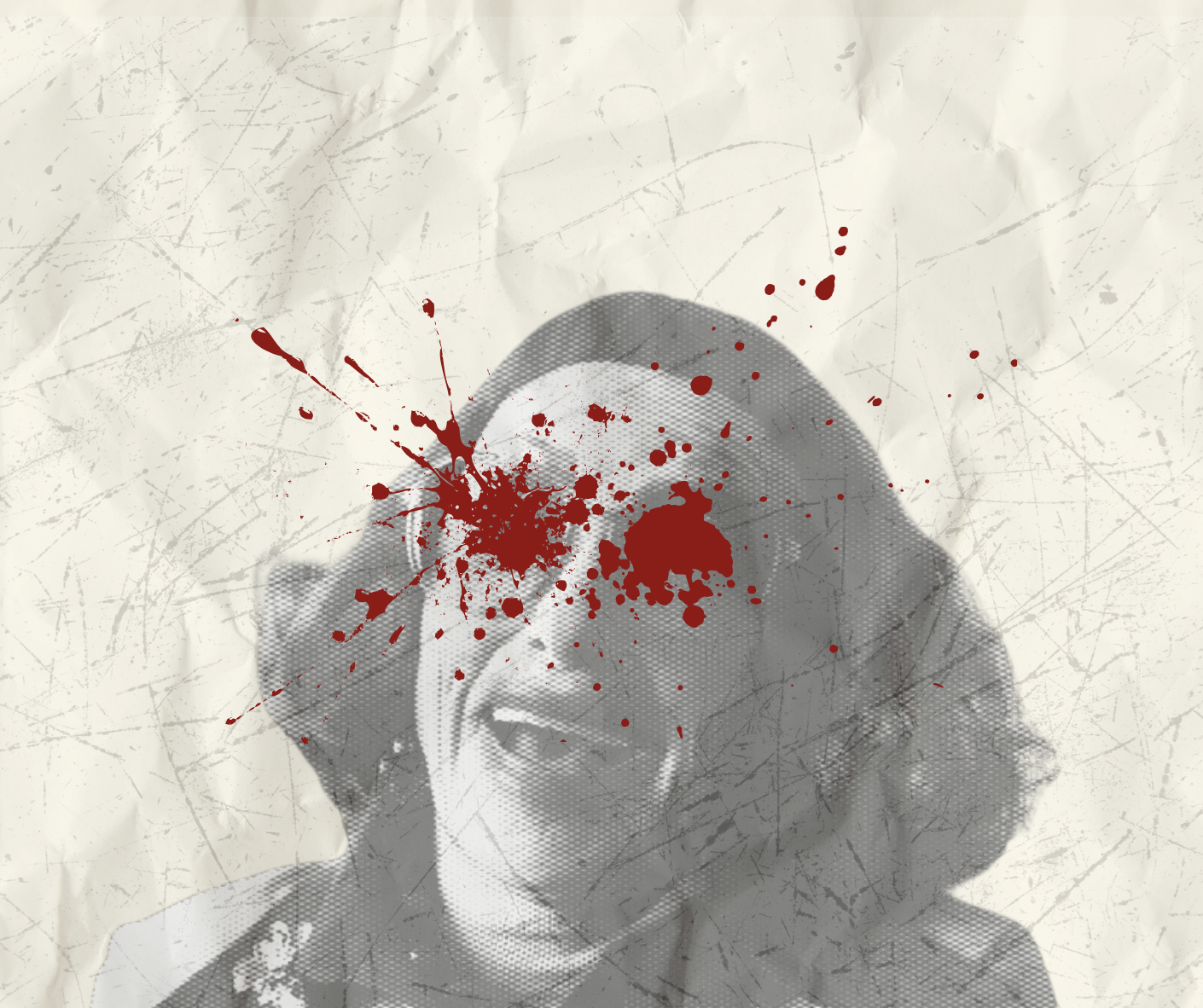

Inspired by Zach Cregger’s 2025 hit thriller, we examine how that which we do not know can either dull fear or sharpen it.

While tuberculosis causes people to expel matter from their bodies, it once bore a name suggesting the opposite: it was called “consumption.”

Those who have seen the film Weapons may recall a brief mention of it. In the 2025 thriller about the simultaneous disappearance of 17 children from the same classroom, Amy Madigan’s character, Gladys, uses the term to describe the illness of two other people in the story. “They have a touch of consumption,” she says—a choice of words that leaves the person she is talking to surprised. The film, after all, is set in modern-day rural America, in a world that knows enough about tuberculosis to find that term outdated.

In earlier days, however, it would not have drawn quizzical looks.

According to a study published in the National Library of Medicine, tuberculosis was long known for a range of symptoms: paleness, weakness, and weight loss, chief among them. It could cause violent coughing and even bouts of blood, but it was remembered most for being a slow, wasting ailment that seemed to hollow its victims from within. In Antiquity, Hippocrates called it “phthisis,” a word translated for the English-speaking world as “consumption.” The name was generally deemed fitting since the illness appeared to devour its host from the inside until death came.

For centuries, this was more or less all that the world knew of the disease. Tuberculosis was cloaked in mystery. People didn’t know exactly what it did, where it came from, or why it chose some and spared others. And that uncertainty shaped the way people coped with it.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the disease’s trajectory and public perception diverged sharply along class lines.

For the wealthy in the West, “consumption” was filtered through a romantic lens. Its visible symptoms aligned with prevailing beauty standards: women prized pallor, thinness, and a languid demeanor—an aesthetic mirrored by many who had the disease. Poets and painters reinforced the ideal, often describing consumptive women as “ethereal.” Even Lord Byron, never one to shy from vanity, quipped, “How pale I look!—I should like, I think, to die of consumption… because then the women would all say, ‘See that poor Byron—how interesting he looks in dying!’”

The disease’s cultural cachet was further bolstered by its famous sufferers: John Keats, Frédéric Chopin, and the Brontë sisters among them—figures held up as tragic geniuses, their illness adding an extra sheen of intrigue.

Then there’s the pace by which it progresses. Unlike cholera, which killed swiftly and grotesquely, “consumption” in the upper classes often advanced slowly over years. That allowed for the public performance of illness: farewell letters, sentimental visits, and genteel suffering. It justified the “rest cures” available to the wealthy—sojourns to rural sanatoriums or warmer climates, thought to slow the disease. And when death finally came, it often arrived to them in the comfort of their homes, as they were surrounded by attentive care, immortalized in art, poetry, and obituaries.

In other words, “consumption” could be a stage for the upper class. Rather than despairing, some sought to turn the illness into a source of social capital.

This isn’t normally the case for the poor.

For those of limited means, the romance stripped away quickly. Symptoms limited their ability to work, worsening already precarious lives. Crowded housing, poor sanitation, and malnutrition not only intensified the disease’s toll but also fueled its spread—conditions whose dangers were not yet fully understood. In small, impoverished households, the disease could claim both breadwinners and children.

Without the means to rest, travel to sanatoriums, or afford nutrient-rich diets, working-class families often saw the illness run its course in months rather than years. While the wealthy could sometimes extend their lives and, in doing so, turn decline into a public drama of beauty and loss, the poor endured a swift, unglamorous, and devastating sentence. Whatever mystery surrounded “consumption,” it was a luxury they could not afford to indulge.

That mystery would not last, however. By the late 19th century, tuberculosis had been stripped of its chiffon and candlelight, reduced to the blunt precision of a clinical diagnosis. The romantic veil frayed in 1882, when physician and microbiologist Robert Koch identified its culprit—a bacterium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, capable of leaping from one set of lungs to another. With that unmasking, the illness ceased to be a poetic wasting and became an airborne threat. Pallor no longer looked artistic; it looked contagious.

The word “consumption” also began to seem quaint, evasive, even dangerous, and was replaced by the sharper, Latinate “tuberculosis.” The imagery shifted, too: gone were the golden-lit deathbeds artists portrayed it with, replaced by sanatorium wards lined with identical deck chairs, patients swaddled in blankets under alpine air, breathing on doctor’s orders. Public health campaigns, armed with germ theory, taught people to see coughs as warning shots and open windows as weapons. Today, the use of “consumption” lingers only as a relic—along with the mystery that once made its slow cruelty appear romantic.

A similar transformation plays out in Weapons. The film begins with a narrator recounting how, one morning at 2:17, all but one child from the same classroom slipped out of their homes, ran to an unknown location and vanished. Just like that, 17 students under a single teacher were gone. The search for answers brought tense moments and jump scares made sharper by how little the audience—and the protagonists—knew.

Eventually, the reason for the disappearances was revealed, a culprit unmasked, and the film shifted. From an unsettling, enthralling mystery, it became a blunt and urgent monster flick. By the end, there was a clear problem, a clear solution, a target of ire, and a predictable set of paths for the story to take. The suspense lingered, but the terror had dimmed.

Such is the effect of knowledge: it curtails suspense, confines the imagination, and robs us of the mysteries that can make life beautiful—or terrifying. But life is never runs out of mysteries even for the old. Thus, it never runs out of sources of beauty or terror. What it tends to run out of is time, though—time that can be made even shorter by diseases or threats that thrive simply because little is known of them.