On the anniversary of its release, we look back at the iconic Lino Brocka film that remains relevant to this day.

People who live in Manila know it as a chaotic and crowded city where ambitions, the means to achieve them, and the forces that stand in their way coexist side by side. This means at least one thing: that it hasn’t fundamentally changed since famed director Lino Brocka portrayed it decades ago.

It was 1975, just a few years after Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. declared martial law. Brocka, a vocal critic of his regime released a film that portrays the capital city under his rule: “Maynila, sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag.”

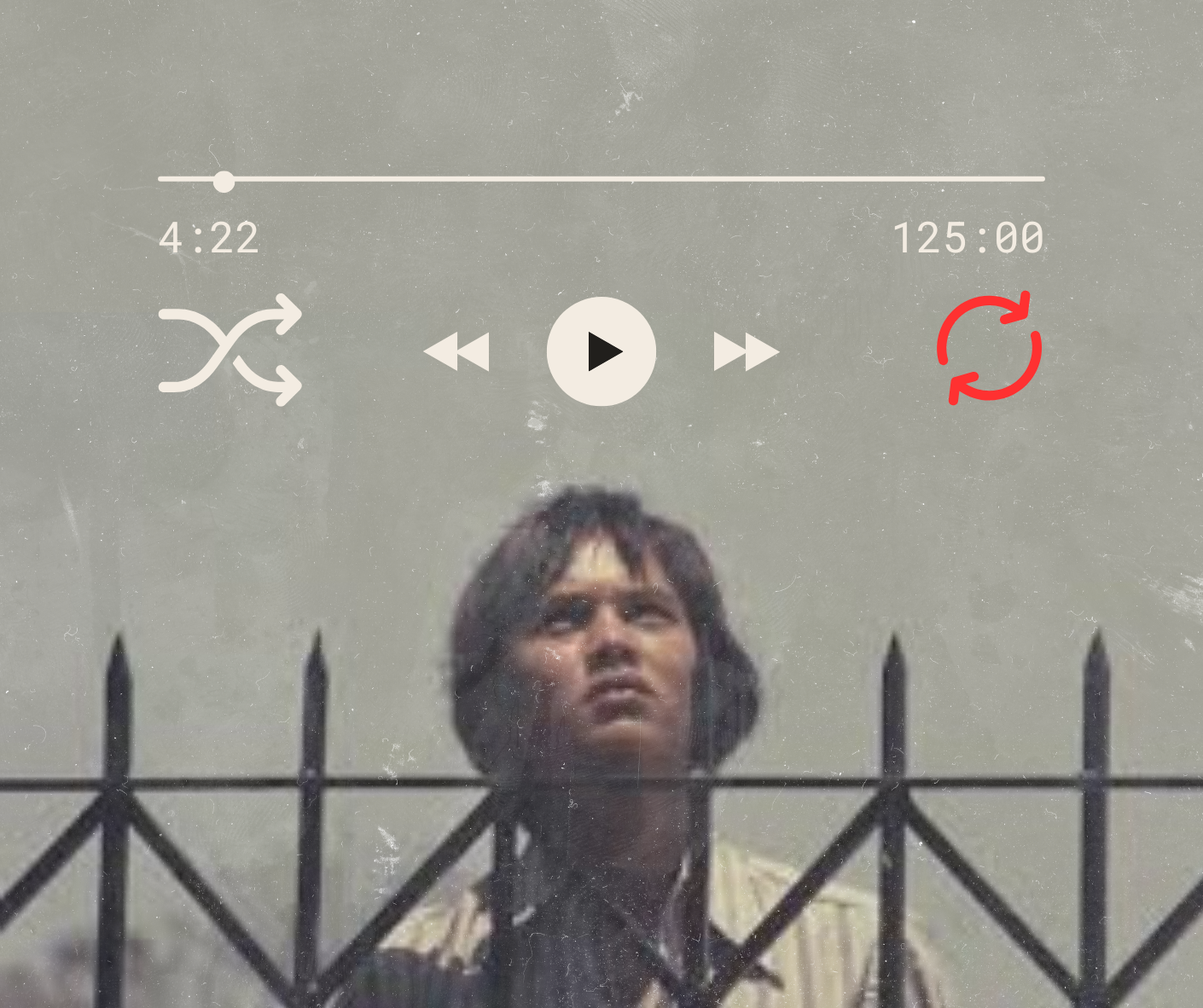

With the English title “Manila in the Claws of Light,” the film follows Julio Madiaga (played by a then-debuting Bembol Roco,) a poor fisherman from Marinduque who journeys to the capital in search of his lover, Ligaya Paraiso (played by Hilda Coronel.) Ligaya (whose name fittingly means “happiness” in English) had been lured to Manila by a woman who promised her work, education, and the means to lift her family out of poverty. But then, she went missing, prompting Julio to act.

During his difficult search throughout the streets of Manila—a quest that drained him of his finances and occasionally left him homeless—he encounters the many contradictions that define a city where the affluent often collide with the destitute. At the construction site he ends up working in to sustain his quest, he finds genuine kindness from his resilient yet underpaid co-workers. But then, he is also met with cruelty from his employer, a man who exploits a system that allows him avoid dignifying his hires with proper wages. If innocence persists in the crowded, mosquito-ridden shanty town that provides an erstwhile roof over his head, he also encounters forces that are more than capable of corrupting it. And when he finds himself among those considered by others to be dreamers (like the construction workers who hope to escape poverty through education or stardom,) he also finds himself among those who see themselves as realists (like the prostitutes and clients resigned to the cold transactions that keep them going.) These encounters collectively pull him away from the innocent and hopeful man who left his province.

Julio eventually reunites with Ligaya in the city. But then came the silent question of the film: can he return her to their province and restore the lives they lost to Manila, or has the city changed them too much for them to be able to go back?

Based on the Edgardo M. Reyes’ novel “Sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag,” the approximately 2-hour film touches upon the subject of unjust labor customs, human trafficking, sex work, urban violence, and inequality—elements present in the big and busy cities where so many can be marginalized. It uses Julio’s quest to provide a gritty tour of Manila rendered through the wisdom of cinematographer Mike de Leon. Through natural lighting, hand-held cameras, and on-location shooting, it immerses viewers into a city populated that puts Julio through a turbulent character arc–one that eventually sees him looking at his hands, wondering how he ended up “here,” driven by something as pure as love.

Its title notwithstanding, “Maynila sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag” isn’t just a critique of the capital city per se. It may come across as a villain here (as many reviewers have been pointing out for the years) but that doesn’t change the fact that it, too, is only reacting to the realities of the Philippines at that time.

The Philippines—especially under the rule of a dictator accused of amassing wealth for himself and his allies—became a nation marked by stark inequality and growing unrest. Progress and the promise of upward mobility were largely confined to select areas like Manila. As a result, the country’s margins were filled with people left behind—those compelled to migrate in search of greener pastures, even if these new places stripped them of power, familiarity, and a true sense of belonging. It was this system that led people like Ligaya to leave their homes and put themselves at risk for a better future.

Set in the mid-1970s, some aspects of Julio’s story may seem outdated today. Technological advancements, for example, could have made it easier for him to spy on people—like the woman who lured Ligaya to Manila. These same tools might have also opened up alternative ways to earn quick money beyond the means he tried (noncontractual construction work and prostitution.) Yet, with new opportunities can come new forms of exploitation and marginalization. And while the country is no longer under the rule of Marcos Sr., many public officials accused of prioritizing personal and political gain over public service have taken his place. Furthermore, the country is once again under Marcos rule—his son won the 2022 presidential election, aided by widespread efforts to sanitize his father’s legacy.

All things considered, demonstrations demanding better treatment of the working class remain a familiar feature of life in the Philippines. Many still uphold systems that keep the poor in poverty to be easily exploited by the rich who wish to get richer. And people still migrate to places like Manila in search of something better.

Somewhere out there, a Julio is still walking around Manila in search of his “Ligaya”—perhaps right before he loses himself.