From Winterson to Woolf, these works of fiction use queer characters to tell universal truths.

Whenever we open our doors to queer individuals, we also tend to open our doors to all that they can offer as people.

This is one of the strongest arguments in favor of diversity. Countries—even those that now lean toward xenophobia—have long benefited from the richness of different cultures brought in by their minorities. Companies that embrace inclusive hiring practices attract a broader range of talent, making them more adaptable, innovative, and productive. And, individuals who are open to others often end up more informed, flexible, and well-rounded. The same can be said of those who are open-minded when it comes to fiction.

Throughout history, many authors from various parts of the world have written about members of the LGBTQIA+. While some have distanced themselves from such writings, there are those who have chosen to consume them, and they didn’t regret that choice.

After all, many of these books—particularly the ones on this list—are well-written, compelling, and rich with insight. And while their queerness might feel unfamiliar to readers outside the LGBTQIA+ community, the themes these stories explore can still resonate with them.

You don’t need to be queer to understand how love can lead you to greatness or ruin. You don’t need to be queer to know the pain of being oppressed, neglected or invalidated. More importantly, you don’t need to be queer to recognize the humanity in those who are—the very thing that makes them worthy of the dignity and equality they’ve been collectively struggling to achieve.

“Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit” by Jeanette Winterson (1985)

English author Jeanette Winterson’s novel—featuring a protagonist also named Jeanette, a thinly veiled version of the author herself—follows a young girl from a working-class family in the North of England who grows up in a deeply religious household. It’s practically required reading for the Sapphic set—a virtual Baltimore Catechism for young lesbians coming of age in the ’90s and 2000s.

See, Jeanette’s mother is deeply involved—arguably obsessed—with the local Pentecostal church. At just seven years old, Jeanette is already being groomed by her mother for a future as a church missionary.

With sinewy prose and a signature flair for lyrical language, Winterson tells a story that anyone raised in a religious household—or a cult—will likely recognize. The figure of the strict, conservative mother, for whom everything is a binary, will feel especially familiar to many Southeast Asians. “[Mother] had never heard of mixed feelings. There were friends and there were enemies.”

A coming-of-age tale, the story shifts when Jeanette meets Melanie, a girl who works at the local fish stall. Through her, Jeanette begins to realize it’s possible to question the sanctity of religion: “[Melanie] stroked my head for a long time, and then we hugged and it felt like drowning. Then I was frightened but couldn’t stop.”

As Jeanette’s feelings for Melanie grow more obvious and impossible to deny, the friction with her mother intensifies—as does the realization that the weight of her faith, and her mother’s oppressive love, may be too heavy to bear. “It all seemed to hinge around the fact that I loved the wrong sort of people. Right sort of people in every respect except this one; romantic love for another woman was a sin.”

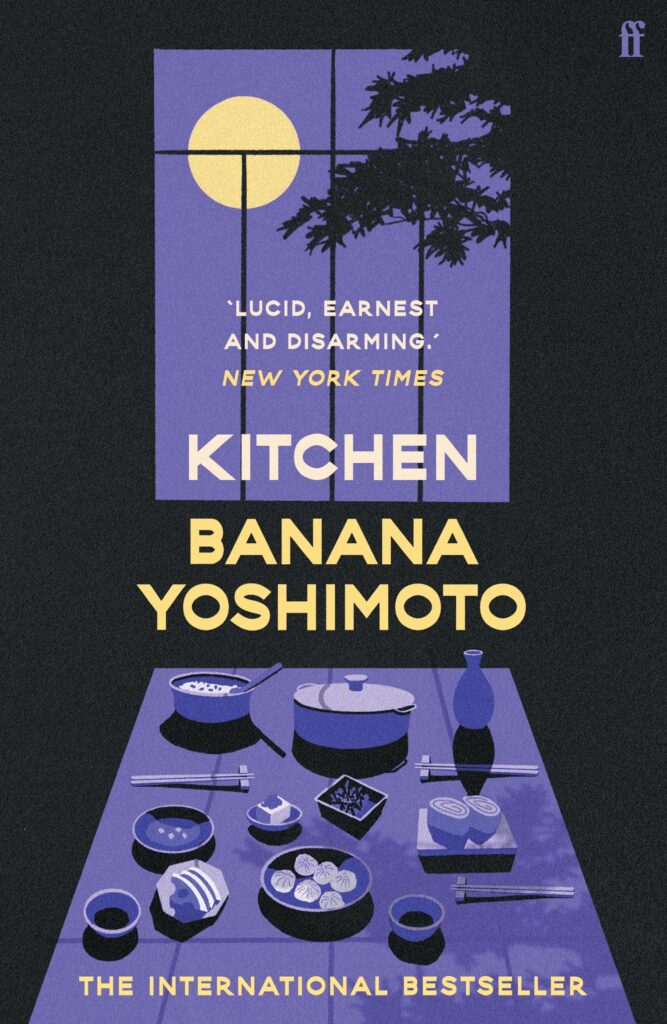

“Kitchen” by Banana Yoshimoto (1988)

“The place I like best in the world is the kitchen.”

The book that started the whole Bananamania craze in the late 80s and 1990s, Banana Yoshimoto’s short novel (actually composed of two linked stories) about the kitchen-loving Mikage Sakurai. With only one living relative left, the very lonely woman sinks deeper into depression when her grandmother dies. She finds comfort from her grief only by cooking in her apartment kitchen, until she receives an invitation from Yuichi Tanabe—a friend of her grandmother’s—to move in temporarily with him and his mother, Eriko. She gladly accepts and is soon back on her feet.

A disarming novel in its simplicity and brevity (clocks in at only 100+ pages,) the way Yoshimoto writes about handling grief and finding kindred spirits is at once heartbreaking and strangely reassuring. At the core of the story is how she posits a transgender woman, the generous and fearless Eriko (who was once Yuichi’s father, now his mother,) as its most positive and wise character. She makes Mikage feel at home and helps her until she’s finally cooking for a local TV show. Through it all, Mikage and Yuichi find redemption from their grief by clinging to each other through adversity.

It was also incredibly progressive for its time and its country of origin, featuring a trans character and fringe cultures in 1980s urban Tokyo. This is a novel that is at once a meditation on the depths of despair and a refusal to be overwhelmed by it, to be held down by that oppressive hand.

“Jammed between my own bags, stooped over, I sobbed. I had never cried this way in my life. As the hot tears poured out, I remembered that I had never had a proper cry over my grandmother’s death. I had a feeling that I wasn’t crying over one sad thing, but rather for many.

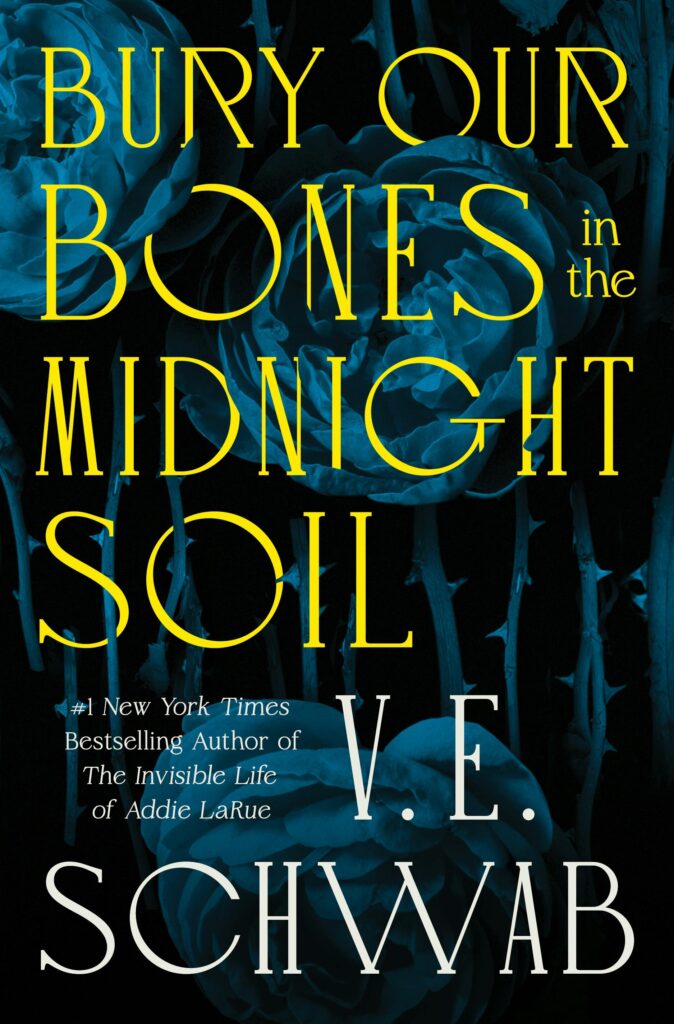

“Bury Our Bones in the Midnight Soil” by VE Schwab (2025)

“Bury my bones in the midnight soil, plant the shallow and water the deep, and in my place will grow a feral rose, soft red petals hiding sharp white teeth.”

If you thought the time of the literary vampire had died out with Anne Rice and Stephen King (somehow, they always find a way to remake Salem’s Lot!) then VE Schwab will prove you wrong with this epic of a novel. A story of hunger for blood and Sapphic desire, this book follows three women across centuries as they navigate class politics, sexism, coming to grips with becoming a supernatural predator, and truly how hurt people can hurt people even through hundreds of years.

There’s such a great tone and approach about the intimacy and tyranny of abuse and grooming but Schwab also asks: “Is it life, if there is never death to balance it? Or is its brevity what makes it beautiful?” Do we attract our abusers like unerring magnets as much as we secretly yearn to surrender to domination?

From Maria in 16th-century Spain, Charlotte in 19th-century England, and Alice at Harvard in 2019 suffering from probably the worst effect of the most awful one night stand, Schwab is expert at interweaving the stories of these queer women through history as they search for love and wholeness while dealing with the cravings of the fang.

The supernatural may be the premise and backdrop, but the meditation on queer identities will ring familiar.

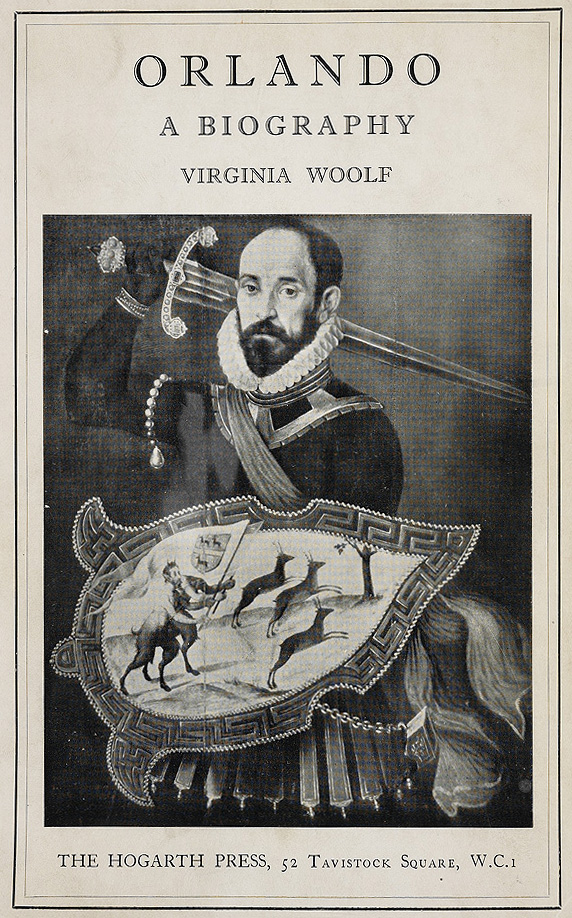

“Orlando: A Biography” by Virginia Woolf (1928)

Is everybody still afraid of Virginia Woolf?

You’d be surprised with this one if you were previously intimidated to read any of her books. A novel written in 1928 about an innocent aristocrat who journeys through 400 years of English history, first as a man, then as a woman obviously isn’t like the other stuff in Woolf’s material. It’s funny as hell and the 1992 movie starring Tilda Swinton (directed by Sally Potter) also reflected that.

Orlando is unique among Woolf’s characters. Plus, the sense of humor is really what makes this one enjoyable, as if the author were on a holiday, clearly having fun while writing.

The narrative lynchpin here is about the protagonist’s sudden and unexplained change in sex from male to female. Orlando does this with grace and Stoic decorum. Seeing for the first time in the mirror after the change, she tells her reflection: “Different sex. Same person.” Which will be infinitely relatable for anyone with body dysmorphic disorder.

A true satire about what we usually think of as a biography, it’s most entertaining when Woolf pokes fun at the social norms of her day. Like the idea of “the Good Woman” in the late 1920s: “if the spirit [of the age] had examined the contents of her mind carefully, it would not have found something highly contraband for which she would have had to pay the full fine.”

“The Song of Achilles” by Madeline Miller (2011)

You’ve probably watched “Troy,” the 2004 Wolfgang Petersen movie starring Brad Pitt and Eric Bana duking it out in the Trojan War.

Obviously, plenty of that was altered to fit Hollywood dramatic requisites. But in her book, American novelist Madeline Miller delves deeper into Homer’s “Iliad” and says the quiet part out loud: that the relationship of the legendary Achilles and his best friend (not nephew, like in the movie) Patroclus was beyond brotherly.

“The Song of Achilles” is a love story. Specifically, it’s a gay, coming-of-age love story about Achilles and Patroclus growing up together in heroic military college, finding their love for each other, then going off to the Trojan War.

Years later, now that the novel has become a literary modern classic and couples are throwing direct quotes for their wedding vows, Miller has described in interviews how she first had to overcome her fears of a classical backlash from the academe to write the book.

“I’d read Plato’s ‘Symposium’, where Achilles and Patroclus are not just presented as lovers, but the ideal romantic relationship. I knew that interpreting their relationship as romantic was a very old idea, and I was angry at the way homophobia was erasing this reading….[I’ve since] heard from people who said it helped them come out to their parents, and others who said it inspired them to get their PhDs, or to start their own novels.”

Miller’s got gorgeous and effortless prose, but she also has a great grasp of this first-person narrative: Patroclus’s voice is distinct and relatable as the one who gets left behind.

“The never-ending ache of love and sorrow. Perhaps in some other life I could have refused, could have torn my hair and screamed, and made him face his choice alone. But not in this one. He would sail to Troy and I would follow, even into death.”

If you know your Greek mythology (or watched the “Troy” movie,) you know that Patroclus died on the Troy beach when he put on Achilles’ armor to lead the Myrmidons on an attack. It was his death at the hands of Hector, Troy’s hero, that sent Achilles into such a rage. The guy returned to the fray, killed the Trojan general (desecrated his corpse too, by dragging it behind his chariot,) and turned the tide of war in favor of Agamemnon and their invading force.

Previously, Achilles had withdrawn from the fighting to sit out the battles and sulk in his tent because Agamemnon had slighted him. Denying the army his elite forces meant bad news for the invaders. Patroclus couldn’t stand to watch his fellow Greeks being slaughtered by the Trojans and so led the sortie. Achilles was so angry that his childhood best friend and lover had died that he took it out on a whole city. Homer’s opening line in “The Iliad” was all about this demi-godly breakdown: “Sing, muse, of the wrath of Achilles.”

At some point, we realize that this is both a fantastique love story about demi-gods and fabled wars and a ghost story. It is the earthbound wraith of Patroclus (his ghost is a character in Book 23 of “The Iliad,” really!) that is narrating this tale, still tethered as he is to the tomb of his beloved Achilles (who died with the famous arrow to his heel) and to the soil of a sacked Troy.

Ultimately, it’s a 400+ page elegy to immortal love, unbent by death, that only knows resolution in the afterlife: “I could recognize him by touch alone, by smell; I would know him blind, by the way his breaths came and his feet struck the earth. I would know him in death, at the end of the world… And perhaps it is the greater grief, after all, to be left on earth when another is gone.”

You do not need to be queer to understand and relate to that.