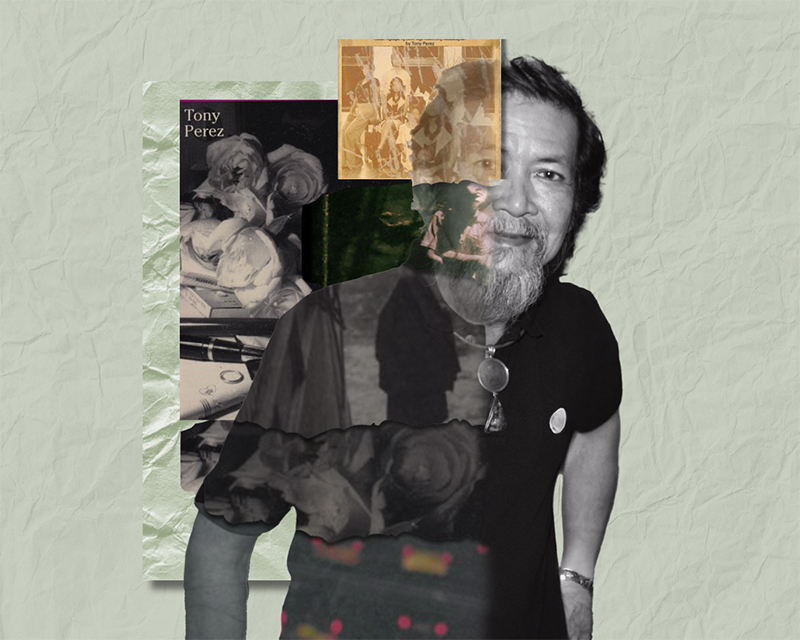

The multidisciplinary talent may have left us at 74 but the impact of his work remains. We look into this by remembering a series of works set in the Quezon City district he called home.

–

The district of Cubao, a hub in Quezon City, has a wide variety of faces and a lot of them have been successfully depicted by a writer who knows many things.

His name was Tony Perez, a giant in Philippine arts and letters. We lost him at the age 74 on May 20, 2025 but the impact of his work remains with us.

There are many hyphenates in the world of Philippine literature who practice other liberal arts and execute them well. But, Perez was a unique soul even among them.

He didn’t just write in two languages, or even just pen landmark fiction, theatrical plays, essays, and screenplays for film and TV; he was also an accomplished painter and visual artist. He held two master’s degrees: one in clinical psychology and another in religious studies. For a long time, he also served as the US Embassy Cultural Affairs Specialist (since the late 1970s) and was instrumental in fostering good relations between our nations through sociocultural interactions.

In 1998, he was awarded by the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) as one of the 100 Culture Heroes of the Centennial. The following year, he received the Balagtas Award for Drama and Supernatural Literature from the Gawad UMPIL (Unyon ng mga Manunulat sa Pilipinas) among others.

Most of all though, he was a true occultist. As a scholar of the supernatural arts, he founded the Spirit Questors in 1996. Eventually, he started recruiting members, advising this group of young Filipino mages and psychics on how to harness their powers to literally become intermediaries between the invisible world and we folks of flesh.

From a class on “Psychic Powers and Shamanism” (an elective taught by Perez at the Ateneo De Manila’s Interdisciplinary Studies Program,) he and the Questors also travelled around the country conducting workshops on various occult disciplines. They also responded to issues that plagued people—those having trouble with ghosts or supernatural entities—and did their best to communicate with the beings and resolve them for the humans involved.

By the 2000s though, he’d retired from “questing,” passing on the group’s affairs to a council. The move to abdicate leadership ensured the organization wouldn’t devolve into a cult of personality—something that Perez detested.

I sat down for an interview with him for a glossy magazine back in the ancient days of the mid-2000s. I remember he confessed that his earliest memory about the world not being as mundane as it seemed started when he saw a white lady in his house. He was 13-years old back then, a young man left perplexed and astonished by the sight of the ghost. Nobody else could see the woman except he and the household help.

“It was a hard time because I didn’t have friends who could see the same things, no teachers who could guide me, no books on the occult here,” said Perez.

“There isn’t a single copy of my books at home,” Perez also told me.

He casts a particularly long shadow across Filipino horror, especially in his fiction. Because he wrote practical magic manuals in his Transpersonal Series as well. Particularly for his “Cubao” Series of fiction and poetry that proved influential to local authors (including myself) who wanted to reflect the daily life and realities of the Filipino into their stories of darkness.

His “Cubao” collection, written in Filipino and almost all of them published by Cacho Publishing House, slanted towards psychological and supernatural horror. His stories made his beloved district in Quezon City (where he long resided,) a sinister world that hid the miraculous, transcending the collision of suburbia and commercial hubs, crowded bus stations and decaying streets, staunchly working-class yet yearning for urbane sophistication.

The Cubao stories are, he told me during the same interview, a product of those old “Tales from the Crypt” comics he grew up with and loved. And now, as we say goodbye to him, we look back at the world he left behind—the Cubao that he had enough knowledge and wisdom to properly depict on the pages of his books.

Cubao 1980 at Iba Pang mga Katha: Unang sigaw ng Gay Liberation Movement sa Pilipinas (1992)

From sexually explicit content to ruminations on the social burdens of living as a gay person in the 1970s and 1980s, this book’s novellas are almost a Baltimore Catechism to the budding liberation movement that was, back then, a far cry from today’s organized LGBTQIA+ milieu.

“Ikalawang Liham, Kay Y” and other stories here are freighted with the yearning for love, predisposition to violence, and the almost physical hunger of desire juxtaposed against the burgeoning district that somehow seemed both magical and savage.

This tone would expand and contract but always inform the rest of the Cubao books that followed.

Cubao Pagkagat ng Dilim – Mga Kuwentong Kababalaghan (1993)

Dubbed as an adventurously brave experiment in the Filipino short story, Perez

expanded his mythical and psychological inquiry further into the shadow realm with fantastic and horrific stories.

Somehow, Perez managed to seamlessly marry the interiority of his characters (sometimes mad, always primal) with the chaotic reality and historicity of Cubao that was now in the throes of full blown urbanity.

One of the landmark stories here that stayed with me was “Ang Mga Manananggal.” Ostensibly a stalker story, it’s about the young and virile Dale who desires the Manayon Sisters—two beautiful young girls raised by a strict guardian. In public, the sisters would dress ultra modestly, and dress alike, too—like twins. But as Dale manages to follow them on their mysterious excursions at night, into the backways of public markets and other seedy locations, he discovers that the sisters have a more erotic and far more sinister side. It’s a story where desire and death collide and mix, a savage yet necessary phenomenon. The twist is great and unpredictable. I won’t ruin it for you.

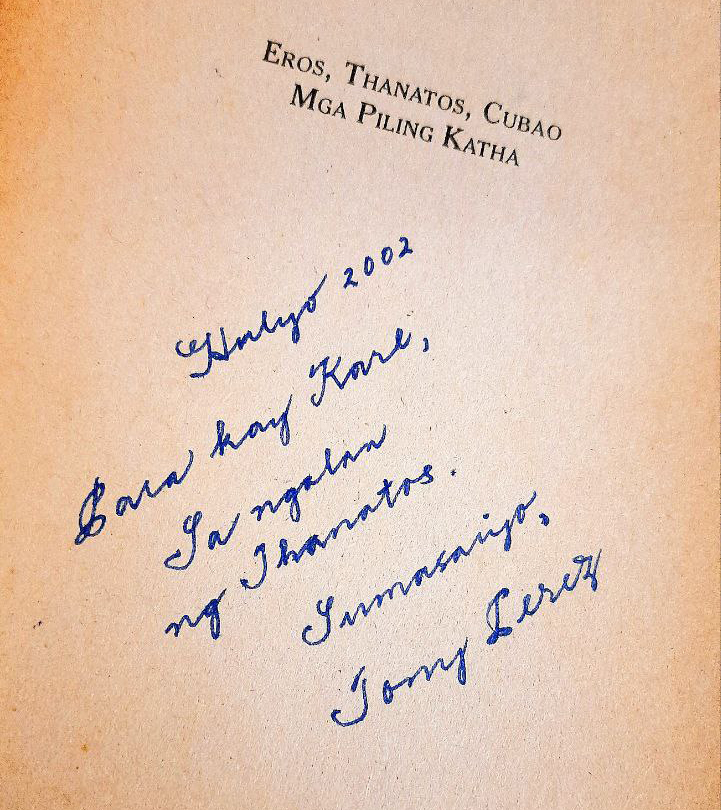

Eros, Thanatos, Cubao (1994)

I had this book signed in the early 2000s and is my favorite among the Cubao series. For me, this is Perez at the height of his literary powers.

It’s also got a great gimmick. There’s two covers, one on each side, bound back-to-back. The stories about love and longing are on one side (the “Eros” side), then if you flip the book and go to the other side, the stories about death and mayhem are on there (the “Thanatos” side).

It urges you to read one side before the other, depending on whether you think you are a Thanatos or an Eros. “If you want the thrill of mystery and the challenge of perils and fighting, you are a Thanatos person.” States the Thanatos side. “If you seek the vitality of life, love, and the welfare of the world, you are an Eros person.” Goes the Eros side.

One of the best stories here is “Pork Empanada,” where a casual, daily evil ruins the health and lives of two street kids who just want to eat the flaky and delicious treat they’ve saved up for and eventually are able to buy. It ends with: “Around us the world continues its relentless turning,” driving home the point that, contrary to the movies, evil can and does get away sans consequence.

Cubao Midnight Express: Mga Pusong Nadiskaril sa Mahabang Riles ng Pag-lbig (1994)

Bienvenido Lumbera had only praises for this book and if it’s good enough for a National Artist then we’ll go with that, too. Lumbera said that Perez is a rare talent who knows “truth and trueness, living in veracity is the Cubao and the people found in these pages; gallivanting, musing, and conversing, who are products of a sensibility with an admirable sharpness in chronicling and embodying their experiences.”

I also tend to agree with Lumbera about how the depth of insight into the many kinds of love is much more pronounced than Perez’s talents for character realism. Vanilla love, horrific love, unrequited love, dysfunctional love, and (my favorite) twisted love.

Look to “Pamamanhikan” for a great, creepy exposition on loneliness and the mind of a serial killer. Seems even the hunter of men need TLC. That the hearts involved always end of broken one way or another is the only guarantee on a ride on the Express.

Cubao-Kalaw, Kalaw-Cubao (1995)

The title is of course the route the district jeepney travels from Quezon City to Manila, and back. This is also Perez’s thematic ourobouros, coming to grips with his very own post-trauma world that somehow repeats like a karmic wheel. Funny that, since this is the last of the Cubao core series.

The book begins with a crime, something that prefaces the events of the story itself and haunts the characters involved. A pedophile kidnaps a child and a cop pursues him. During the chase the kidnapper kills the young one and eventually the criminal kills himself, too. From this heinous and savage act the novel unfolds in the ripples, in the child of the criminal, the sibling of the victim, and in the adopted child of the cop who chased them down. All separate yet connected through Perez’s clever, wry telling.

While it’s certainly a crime novel, there’s a lot of big themes and issues that Perez, I believe, was trying to come to grips with here. Everything from poverty to nationalism, failure to manage post-colonial pains and our dire need for a collective exorcism.

“Cubao Ilalim: Unang Aklat” and “Ikalawanag Aklat” (2021)

Perez was relentlessly writing and released books up until his final years.

In these “spin-offs” of the Cubao series Perez imagines that the kingdom of Berbanya (from “Ibong Adarna”) exists below Cubao and his hero, magic expert Mang Jony, is the investigating intermediary between this mythical realm and the cities of man as we know it.

This “underground” mythos veers away from the stark realism of the core Cubao series and goes full fantastic, merging its urban fantasy in the vein of Charles De Lint and Neil Gaiman into familiar locales like Araneta Center, Broadway Centrum, and P. Tuazon Street.

Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino made a great decision to release this fantasy adventure by Perez. Many Jony’s adventure into the Cubao Ilalim and his encounters with Rey Morales (the books’ analog of Haring Salermo) and others from the classic legend make for a quite enjoyable, arguably light, and far less psychologically sinister read than the previous “Cubao” books.