The writer of the Dreamland trilogy talks about the importance of finding humanity in both the oppressed and their oppressors.

Nobody is without sin in the writings of award-winning fictionist Ronaldo Vivo Jr.

In certain literary circles Vivo is esteemed as a cult figure who’s authored three gritty Filipino novels of crime and noir. “Ang Kapangyarihang Higit sa Ating Lahat” (The Power Above Us All,) followed by “Ang Bangin sa Ilalim ng Ating mga Paa” (The Abyss Beneath Our Feet,) and recently “Ang Suklam sa Ating Naaagnas na Balat” (The Loathing Within Our Rotting Flesh.)

Those three books officially compose what the writer calls “The Dreamland Trilogy,” named after the sprawling Pateros slum Dreamland where the novels take place.

Though they are technically stand-alone books (where a reader can pick up any one as a way into the world of ordinary decent criminals and murderous cops that inhabit Vivo’s milieu,) they’re best read chronologically. This linear process rewards one with the observation that, albeit there are different protagonists per book, their lives do intersect and each one is often involved in the same events—like six degrees of criminal separation.

These works have also feted him with a finalist award for both the Madrigal-Gonzales First Book Award and the National Book Awards for novels. He’s also the recipient of the Gawad Bienvenido Lumbera for short fiction.

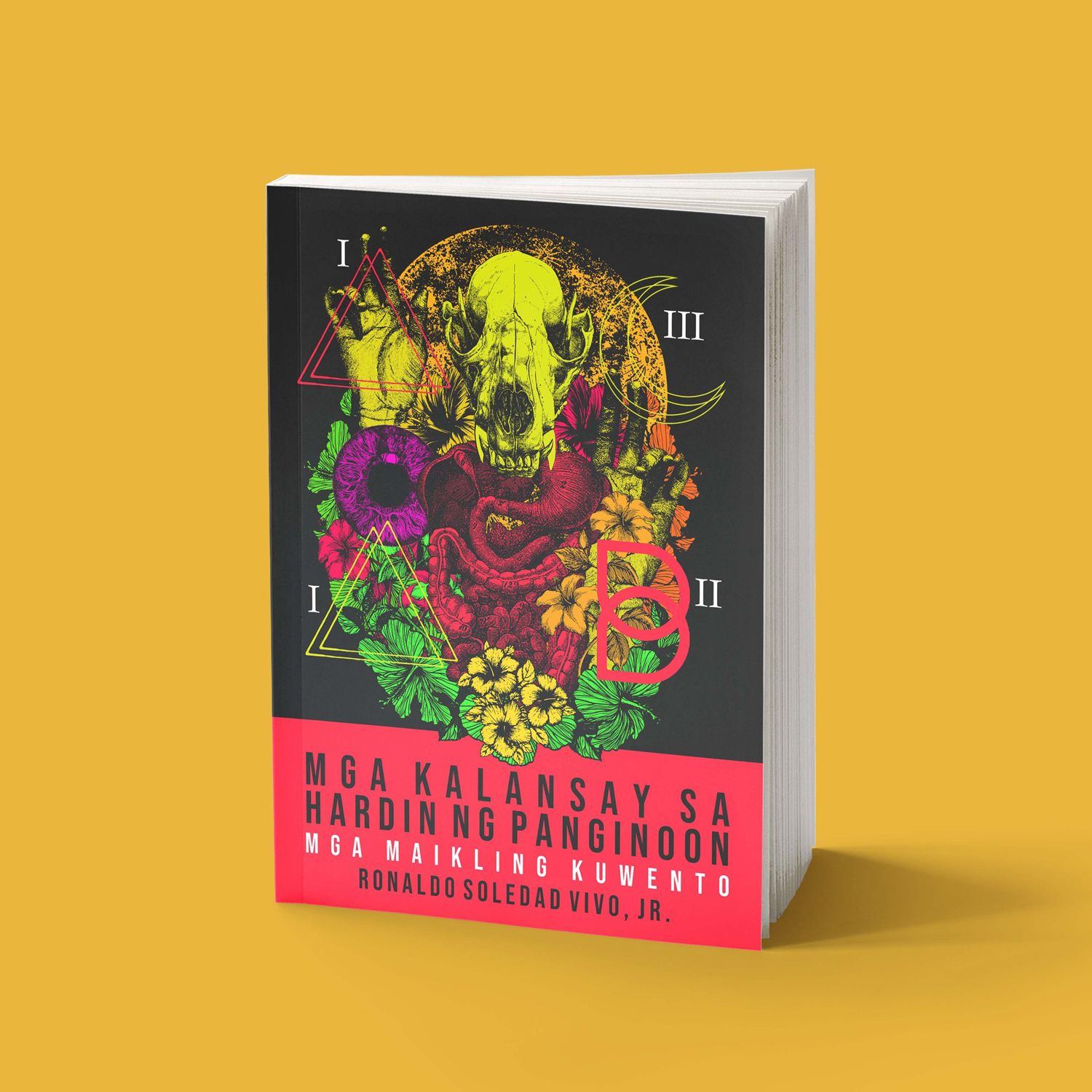

In late 2023, Vivo released his first short fiction collection “Mga Kalansay sa Hardin ng Panginoon” (The Skeletons in God’s Garden.) With seven short stories collected from 2012 up to its release date, like his novels, it quickly became a cult hit that sold out at UngazPress, the independent publishing house Vivo and his friends run. A larger publication batch is forthcoming soon, this time with a mainstream publisher.

Similar to his novels, the stories in “Kalansay” are definitely not for the faint of heart. Though he calls these stories “my writing artifacts before Dreamland,” his words remain as sharp as the authentic Filipino inner city vernacular that permeates his longer works.

“…A tapestry of violent histories of contemporary Philippine society,” is what Melbourne-based poet Christine Lining Bulandus aptly called this collection.

Though mainstream literary circles have noted his quick, stellar rise, as if Vivo had simply burst forth from the fringe to achieve cult status overnight, this collection proves that he’s been honing his skills in hardboiled and noir for years.

In “Kalanasay,” he shows how his ear for language and authenticity—the registers and spirit of each place—are crucial. The presence of locality imposes so much on his characters that it’s a character in itself and informs protagonists actions—like bartering one’s own children for a hit or experiencing the agony of a rabies infection.

“How characters speak in certain locations is very attractive to readers,” he said in one of our previous interviews. “I never wanted the people to speak in long and rehearsed lines apt to novels. They should talk like they would in casual conversation. Make it crispy and sharp!”

“There is a different point [of local argot] in Pateros,” he continued. “Different in Las Pinas. Different in Valenzuela. The ghetto of Makati is not the ghetto of Caloocan.”

In September this year, Avenida Books will release the 10th-anniversary edition of his first novel “Kapangyarihan,” with a new cover by noted graphic designer Alan Navarra. But before we get there, he took the time to look back at the fictional yet highly believable skeletons he bared to build his career.

KARL R. DE MESA: What’s the ideal construct or infrastructure of a crime story for you?

RONALDO VIVO JR: When I was writing my first novel, “Kapangyarihan,” I did not intend it to be a crime novel. However, as I moved forward, I learned to embrace it because perhaps my influences can’t really be hidden in my works.

So, if I have been writing crime stories, my definition of it would be a world where the oppressed and the oppressor are both humanized, battling in one melting pot that reflects a country’s history of violence.

KDM: Crime and noir fiction fit so adequately within the Philippine reality; do you feel current literature or popular media represent our milieu well?

RVJ: A lot of great works of literature have been coming out recently, and I couldn’t be happier to witness such an energetic publishing scene.

In movies, it’s evident that filmmakers have greatly evolved in their technical aspects. However, if I’m sticking to my definition of crime/noir fiction, what I’ve always sought in contemporary works is the humanization of despots and the disadvantaged.

KDM:A more nuanced look at both the persecuted and the authorities?

RVJ: I mean, if the intent is to unmask the most violent criminals in this country, you’ve got to at least flesh out their humanity—if indeed they have any. This theme still persists in my search, based on the books and films I have consumed.

KDM:What was your process in curating this collection for release?

RVJ: The stories in “Kalansay” span from 2012 to 2023 and represent my work during that period.

Some of the entries were originally intended for an anthology with my boys at UngazPress. However, as it turns out, getting seven writers to collaborate is tougher than having a band with four members to record an album and play live gigs.

So, after 11 years, I finally decided to collect and publish the stories as a collection.

KDM:And the idea behind the title that ties up all the stories?

RVJ: I tend to title my works as if I’m naming my music projects with Basalt Shrine, Abanglupa, and Dagtum [where I play drums.] Know what I mean? Haha!

“Skeletons in the Garden of God” evokes something horrific amidst the grandeur orchestrated by the rulers of our time. And, man, doesn’t that sound like a hardcore or heavy metal title?

KDM:Novels vs short stories, which do you enjoy working more on and what’s harder to execute for you?

RVJ: Neither form is enjoyable. Writing never gets easy. [Vince] Gilligan said the only enjoyable part in writing is “to have written.” Or the finished product. I share the same sentiment.

But if I am to choose which of the two gives me a harder time, it’s short stories. Short stories have little room to maneuver; you need to hook, jab, and slam in a very limited number of pages. Writing a novel gives me more time to contemplate and set things up in slow-quick burn dynamics.

KDM:In online forums, folks respond plenty to two particular stories: “Walang Imik” and “Catcher.” What’s the inside scoop on them?

RVJ: I wrote these stories when I was 21 to 22, and my juvenile energy was just overflowing. Actually, I have not read these stories for a decade, and when I revisited them, I realized that I don’t think I can write the same stories at this age.

“Walang Imik” and “Catcher” are plain brutal stories. I remember that while preparing the manuscripts for these stories, I felt like I was just doing my usual UngazPress short story.

More than a decade later, I can’t even stand the graphicness of these materials. That’s why I always thank the readers for enduring my works, especially the early ones.

KDM:There’s also lively discussion about the seeming inconsistencies and conflicts in these two stories. How do you feel about the response of readers to these seeming sticking points?

RVJ: I got a five-letter word answer for this: DRUGS.

KDM:Do you have a favored child, as it were, among these stories?

RVJ: My latest short story, “Dianson Park,” is unlike my other works. I really enjoyed writing this one. It’s my fresh take on writing a short story. The characters felt real and close to home—in the ghetto where I grew up. I think I have executed a good balance of dark humor, grit, barangay-level crime, and world-building in this one.

KDM:Who are the authors you admire for short fiction, especially short crime fiction?

RVJ: I have a very short list when it comes to fiction. Dennis Lehane is at the top of my mind. He’s not purely a crime writer by the traditional definition, but I also admire Irvine Welsh’s anti-heroes.

When it comes to films, I have a long list because film is my main influence in writing stories. Of course, there’s Scorsese, Fincher, Gilligan and Gould, the Coen Brothers, Lau and Mak, Johnnie To, Na Hong Jin, Chan-Wook, Je-Woon. I could keep the list going!