A coming of age work of fiction where a brave girl comes to grips with indigenous and modern forces inside and outside of her as she charts her way into the ‘real’ world.

Paracelis boards the bus that will take her to Baguio. Baguio was the city of her dreams, because of what she heard from her mother.

Her mother’s watch hung loosely on her wrist and told her it was 4 a.m., right on time for her to be picked up and accompanied below the village. The village was still asleep, including Grandmother who kissed her goodbye the night before. Before she left for the station with Manang Gawani, Paracelis gazed at everything around her, thinking it might be the last time she would see the place she’d grown up in. In the fading darkness, she made out the outlines of the laddered huts and thatched roofs for the last time.

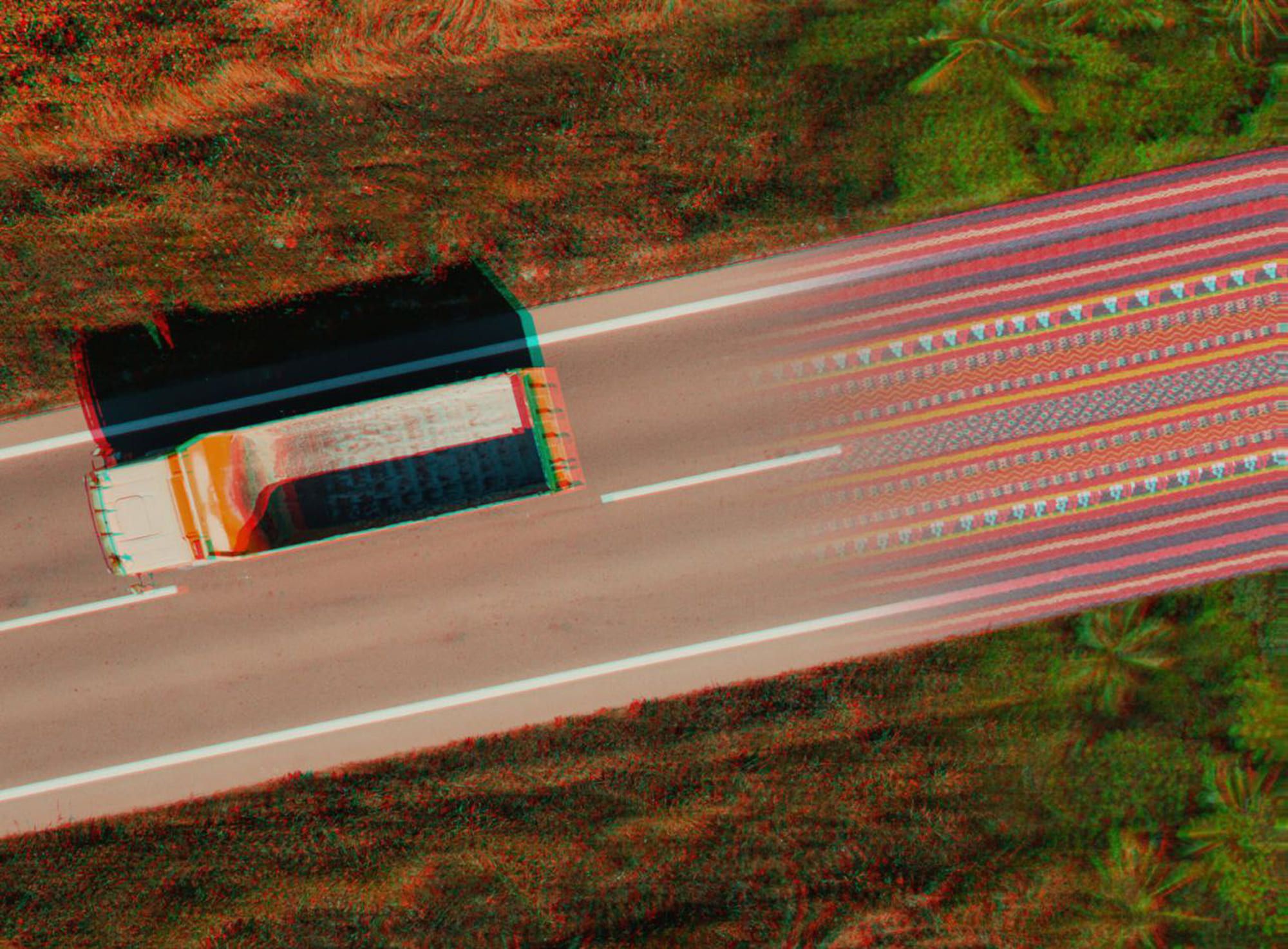

Time was no match for Paracelis’ expectations as she sat firmly in front of the bus, excited to be the first one to get on, then off. Off they went, past the last junction which met the dirt road of the village. The village was hardly seen from the bottom, but as the driver picked up the pace to lead the bus down the valley, she could imagine Grandmother waking up, too late to wave — with tears. Tears that were overshadowed by the embracing forest that grew smaller and smaller as the valley gave way to craggy rocks, ravines, and the dry gorges.

The dry gorges were not there during her mother’s time. Time had not been kind to the Cordillerans, with their welcoming of the lowlanders. Lowlanders and foreigners who professed ‘modernization’ that meant wealth for the miners and loggers who worked hard and ate well. Well enough to bring their large families up the mountains to take in the crisp air while they desecrated age-old forests, threw concrete at everything in their path, and blackened the waters and valleys.

Valleys that Paracelis no longer recognized as the bus made its way past the winding roads that grew wider and smoother, but led to harsher sights—hills increasingly pock-marked all over with shanties where the trees once danced with the wind. Winding down the road as she sensed she was near, Paracelis closed her eyes and thought: “Maybe this is a test from Kabunian: ‘the night is a dark blindfold worn before the daylight makes all things well again’ said her mother.

Her mother spoke of benevolent white men and even whiter cottages. Cottages where she cooked and cleaned for a widowed serviceman with whom she fell in love. Love that led to a child. A childbirth that led to death, a provenance that eluded Paracelis until her thirteenth birthday, one she dutifully celebrated with her grandma. Grandma felt it was time to let her only granddaughter know about the truth, woven with myth, but it would do:

“Apo, was Mother really taken from me by the white anitos, and is this why my skin is so pale?”

“Pale – ha! Your mother left us early but that was her sacrifice for your gift. She watches over you and loves you. The puraw anitos have given you skin like pearls, whiter than any of our people, an amulet that will help you move easily in the world. It was even your mother who said so.”

“So Apo, remember that story you told me about the spirits? Will they help me now?” Now grandmother was already old, and could not quite remember at first. First, she was angry, for she rued the day she could no longer keep Paracelis at home. Home to her was as fluid as her blood, running underneath her bright skin, bringing her to places where she would pursue her adventure and life.

“Life has woven you an unfinished garment. While I do not want you to go, you have been given another gift by the white anitos and their priests, the Episkopalyans who will take care of you in Baguio and then bring you to your father’s world. The world is harsh, you will see, but this village right now cannot contain your spirit nor your mind, my beautiful child.”

“Child!?” Apo, I will soon be a woman, and I choose to leave with this gift, and that’s all I’ve ever wanted, more than this place could ever give.”

“Give your people some respect, Ading. We are unlike anyone in the world outside the village and soon you will see.”

“See, Apo, you don’t get it. Baguio is calling me and I cannot wait to see the beautiful cottages, the beautiful clothes, culture, and people. I want to be modern.”

‘Modern’ was the word for Baguio. Baguio was the summer capital of the gringos, the colonizers who drove off the Kastilas and many of their friars before they could completely destroy the indigenous culture of the Cordilleras as they did in the lowlands. Lowlands that had already become a wasteland of urban blight, poverty, and despair.

…

Despair was the farthest thing from Paracelis’ mind as she folded her woven clothes. Clothes that she was eager to replace with the outfits she saw in one of the magazines her mother had left behind, filled with foreign images so different from Paracelis’ life in the village.

The village was dark when she went outside, shrouded in fog that brings Gaddangs their dreams. Dreams that stir the women to weave these visions through their backstrap looms. Looms that wrought the most unique and beautiful of tapestries—so mystically different, even among all the Cordillera tribes. Tribes that often fought and fought until their culture fell into decline. Decline that the Gaddangs, (because of their isolation from the rest of ‘civilized’ and warring world) would avoid, so far.

So far were their villages that the Gaddang kept to themselves, fended for themselves, and learned to keep their traditions. Traditions that suffused every part of their life — invoked so viscerally by the women weavers into their cloth that physically had the same colour and fabric as the other tribes, but always with one thing more.

More than the warp and weft could do with dreams, the women weavers asked their families—their men, their elders, and their children—to bring them tokens to weave in them: bone, seeds, shells, magic beads, minerals and mementoes. Mementoes that now included Paracelis’ mother’s pearl earrings, given to her by the white anitos, or so her grandmother told her.

Her mother’s photograph, surreptitiously hidden in between pages of one of the magazines, betrayed the truth; for holding mother’s hand but looking away was a milk- skinned man, and Paracelis often recognized his smile in the slowing brook whenever she washed her woven garments, all packed inside her basket, except the one she wore on the ride to Baguio. Baguio after all, deserved to receive her in her best self when she stepped onto the city. The city was ‘sophisticated’, and with her moonlit complexion and mystical attire she might still be able to impress her new guardians. Guardians who would teach her all the new things that might finally take her to her real father’s home halfway around the world. The world was so big after all, and Paracelis felt her heart would beat large enough to contain it.

…

Her eyes welled up from the soot of the diesel trucks that piled up as the city came into view for the first time. Time must be such a cruel god, Paracelis thought, as she saw for herself the city of her dreams. Dreams that bore no resemblance to the syrupy stories that Mother had told her as a little child. Children were running with dark, tattered rags, now coming up to the vehicles, speaking broken English and a dialect she could not comprehend; shouting curses when the drivers or passengers would ignore their cries, with their parents disappearing into the mines or the brothels that had sprouted like rings around this rotting trunk of Baguio.

Baguio looked cruel, lonely, and heart-breaking; and no amount of wishful defiance could convince her there was something better that lay beyond the poisoned hills before her.

Her mental pictures of the white cottages, the benevolent white people, the happy homes and blossoming garden lands were nowhere to be found.</p><p id=””>Founded by the Ibalois, the Gaddangs’ distant kinfolk, Baguio a generation ago was exactly as her mother described and loved. Loved enough to forgo her beloved people and home. Home that she believed Paracelis would also leave one day.

Day announced its arrival through the warmth beginning to pierce the windows as the bus snaked its way through the red, carved mountains with her muted passengers. Passengers, a menagerie of bloodlines, were coming to life one by one. One of them, an i- Kalinga, set aside his miner’s hat, stretched his dark, tattooed arm across the aisle, and tapped Paracelis on the shoulder.

Ading. Mangan tayon

Paracelis’ eyelids are heavy, but she manages to reciprocate. She nods, let his gnarled fingers and knuckles meet her forehead as a benediction to an elder. She can taste her bile from the twists and turns as her excitement waned with her vision. The fog of the early morning but an image in her head, and she feels a strange pain near her belly. Yet in those very seconds, as she traces the bone fragments in her shawl, she feels more serene than the reality outside the bus.

Agyamanak, apu, naimbag nga bigat. She tells the old warrior.

His other arm stretches out, revealing the painful etchings of his forebears. It reveals an unopened orange. She refuses but he insists. His smile, like the sheared mountains, is red- stained with betel nut. They settle on her taking the peel, inhaling its goodness, and she leans her head back as he withdraws to his side and looks outward to the oncoming horizon.

Paracelis knows she is falling into the land of dreams, and she welcomes it as her elders taught her to.

She looks down at her arms and legs and can tell she is much older. She is standing in the mirror. Gone are the beads, and in their place, her hair is tied, its tail peering from behind. Blue walls surround her—not like the sky’s, but like those ponds that she sees near the mineshafts. She doesn’t want to look at her face, and instead turns around to find out where she is. There are books around her, but she cannot recognize nor understand the titles. She steps forward, struggling to reach the doorway. When she reaches for the knob, she pauses, tries to trace the grain on the door. But instead feels the coldness of the slab, unlike her village walls, where each plank retains its life as an offering to the gods for shelter. Little pictures on the wall catch her eye; she moves closer to examine them, almost in a blank stare. In one, she is veiled surrounded by blank, cold mountains. In the other, she is sitting down, surrounded, almost pressed from all sides, by a white, curly orange-haired clan. Not unlike her father, but Paracelis can barely look at the face of her spouse. And in that moment, she fears he is on his way back to their house as the sun fades into the orb of the cobalt den.

She feels paralyzed, wants to leave, but starts frantically looking about. There is a metal steamer trunk near the bed. She rummages through that, then rushes to the opened glass closet to run her hands through the long, shiny gowns, looking for the familiar texture of her missing, woven garments. She can feel nothing visceral in this place. She brusquely seals the cabinet and suddenly, her mouth feels dry as she sees her reflection once more. Behind her, the redness of the horizon looms over the jagged shadows of the glassy towers. In this crimson backdrop, Paracelis sees her skin turn even paler, like drying ivory, and slowly, she begins to feel her life draining from her.

…

Her eyes flutter open as she wakes to a strange sensation, almost like that of a rushing brook beneath her. Her nostrils pick up the scent of fresh blood, reminding her of the ritual preparations of each kanyao in her village, shaved sacrificial hogs, their jugulars opened to drain the unclean and bless the dap-ay soil. Soiled were her thighs, her seat dampened with her womanhood, and she misses her mother, and she starts to miss her. Her fresh woven cloth is all she has, and she takes It from the basket, using its deep red patterns to stanch her pelvis, thighs, and the remaining blood away.

Away beyond the blighted hills, and with her own rite of passage behind her, Paracelis did finally see a small green spot, with a rusted barbed wire fence surrounding it. It’s as if these metal borders were the only things standing in the way of the rotting decay threatening to infect the tiny, lonely pine-shrouded hill that she was approaching.

Approaching the gate, the driver called out: “This is your stop, ading. I will tell Apo Bielmaju you got in fine. Be good, and don’t forget where you came from.”

Don’t forget where you came from—those words kept ringing in her ears, and as the bus swayed to a stop, the sound of her hanging beads rippled through the gated, silent hill and into the trees.

The trees rustled one by one downward, until a white man—not as divine-looking as she had imagined – stepped outside to greet her and take her hand. Her hands were pale, paler than her skin, but soon warmed to the touch of Reverend Peter. Reverend Peter’s smile conquered any fear Paracelis had as they climbed up the steps.

“The steps are steep, dear, would you mind helping this old man up?”

Up the winding path they went, with Paracelis clutching the old man’s arm, the other her reddened tapis skirt as she looked around her new home. Her new home, the Episkopalyan School, was run by the Reverend’s wife Linda, who met the two of them at the threshold, and walked them through the blooming gardens. Gardens that led them to a white cottage, and when they inside, she gave her a warm hug, tighter than her mother or grandmother had ever tried in the past.

Past the bookcases, through the fireplace and into a brightly-lit room, Paracelis was led and left there by Linda until they would serve supper with the other students. Students, she thought, who must be as lonely as her; but instead, all she could hear were songs and laughter. Laughter that suddenly reminded her of the village children, so different and yet so much a part of her.

Her fingers traced the beads of her skirt and palmed the pearls her mother and father had left behind. Behind her was a long journey; ahead, an uncertain way, she thought as she sat down to unpack her things and for the first time smiled through her tears.