Netizens smell trouble as a woman’s “innocuous” post leads to threats of rape and death.

Towards the end of 2024, a teacher from the University of Cambridge reached new heights of fame because of the people who, ironically, tried to bring her down.

Her name is Dr. Ally Louks, and, as a scholar of English literature, she’s been getting a lot of support. Since early December, people from all over the world have been reaching out to her offering encouragement and congratulations. Many have also expressed interest in her work. Meanwhile, her account on X (formerly Twitter,) has gotten so much engagement that the app saw it fit to give her a blue check that she never even requested or paid for. She even managed to earn 14.67 pounds out of it.

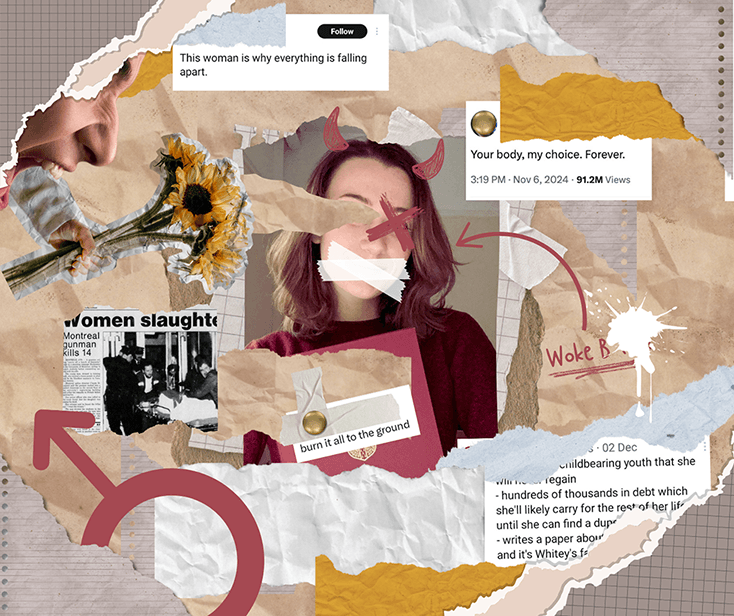

It’s been unusual for the self-confessed introvert. And it all came about because she shared an academic achievement and people started sending her things like this:

“You are the dumbest fucking bitch I’ve seen on the internet,” the sender who found her email said. “The perfect example of literally everything wrong with modern society.”

They then listed supposed aspects of Dr. Louks’ identity (queer, vegan, feminist) as if they’re enumerating crimes before accusing her of thinking that she deserves “taxpayer money” for her work.

“…Your dues to society are many,” they therefore concluded “and me and the boys will RAPE them out of you.”

Dr. Louks has since reported this message to the police.

According to her talks with various publications, it all started after she posted on X, an app notoriously lenient towards brands and personalities that openly thrive on hate speech.

On November 27, 2024, Dr. Louks shared on the app that she completed her PhD program at Cambridge after passing the oral defense of her thesis “with no corrections.” The photo accompanying her announcement had her smiling in a red sweater with a hardcover copy of her thesis. On it, printed in gold was the title: “Olfactory Ethics: The Politics of Smell in Modern and Contemporary Prose.”

Essentially, this examines the socio-political power of language related to smells. She completed it after three and a half years of writing and research.

Looking back at her post, Dr. Louks said that it was “innocuous;” a thing she did merely to inform the people within her field—many were her mutuals in X–that she has become available for postdoctoral work. But while the initial responses to it were kind, wholesome and encouraging, the post soon got out of her small circle of academics and crossed over to the engagement-hungry, blue-check payers of right-wing X. And this was when hostilities began.

The mob that came went after her thesis which many saw as a target for anti-intellectual vitriol. The tamest came in the form of put downs referential to its title (“this stinks!”) Some users meanwhile came after its subject (or, in some cases, what they thought its subject was.) They claimed that it is a weak topic dressed up in hifalutin words and some users tried to confirm this by providing “translations” of her title and abstract. Most, if not all of them, however were actually reductive misrepresentations of the scholar’s intentions.

But, while it remains unclear as to whether or not these were deliberate, it is undeniable that such comments set the stage for other messages. For example: the ones claiming that the academe is “dead” and that people should not waste their time and resources going to long-respected institutions of learning because those are likely to support studies like this.

The attacks, however, weren’t focused on Dr. Louk’s work alone. Some also sought to shame her for pursuing her current path in life. There were users who tried to mock her for “wasting” her time in this instead of pursuing more traditional, “employable” money-making endeavors or starting a family. In a now deleted post, for example, one X user claimed that Dr. Louks “lived in the most advantaged time in all of human history for women” but she has “nothing of value” to show for it and her “bloodline will end” with her due to her “need to stick it to the evil man by getting an ‘education.” In angrier posts and private messages meanwhile, Dr. Louks was met with threats of both rape and death.

Inevitably, such reactions sparked yet another battle in the culture war as people felt compelled to defend Dr. Louks and her work. Academics, for one, praised it for its contents, its potential applications in social discourse and the necessity of the academe tackling niche topics.

“When I was in elementary school,” said Harvard’s Khalil Andani, “the kids used to make fun of us brown kids by saying “you smell like curry so what this academic is studying is a real thing and should not be ridiculed by the uneducated.”

Meanwhile, some called out her detractors, accusing them of attacking Dr. Louks out of sheer insecurity.

“It’s very clear,” said TikTok user Milo, “that a combination of their jealousy at not being where she is in life and their offense at not being able to understand what she does has led to this place where they feel it’s their right to humble her because she’s accomplished so much.”

Historian Bret Devereaux shared this sentiment on X. By his estimation, the “rotten waterfall of hate” received by Dr. Louks can be due to two possibilities. “She got it because 1) some people don’t like her *conclusions* but are not prepared to dispute her evidence or methods like grown ups,” he said, “and 2) some people are hurt that a woman made them feel dumb.”

And the reaction she got is an experience many women on the internet can relate to.

Defined mostly as hatred or prejudice against women, misogyny has, been a constant presence online—especially in spaces where anonymity serves as a shield from accountability.

In recent years, however, as the fight for progressive ideals intensified especially in the loud and proud West, expressions of misogyny (among other beliefs based on prejudice) have grown bolder in an attempt to discourage, disparage or intimidate the women who are championing change.

Several publications noted that there was a recent uptick in this after Donald Trump won the 2024 US presidential elections; a victory he earned even as his campaign threatened the rights of women (especially to self-autonomy.) Following his victory, part of his voter base—right wing men—appeared to have been emboldened enough to harass women online and offline with sexist remarks. Among their favorites was the classic “go back to the kitchen.” Another popular one was pushed into the spotlight by far-right pundit Nick Fuentes: “Your body, my choice”—a patriarchal mutation of the “my body, my choice” battle cry used by people who are pro-choice.

“The masks are fully off now,” one X user commented. And this was a reality many have been warning about years ago.

Online, various groups concerned over the safety of women have brought attention to the manosphere—a collection of websites, forums, influencers and communities both online and offline which encourages misogyny under the belief that society should cater to and prioritize cisgender, heterosexual men–they whose long-held privileges have been repeatedly challenged by feminism and those fighting for the rights of the LGBTQIA+. The men who participate in this are known for espousing sexist rhetoric while advocating for outdated norms that tend to limit the rights of women. They’re also known for loudly pushing back against policies and ideas that threaten their privileges.

Concern over spaces like this stem from the many instances when misogyny was emboldened and validated enough to actually lead to harm–something that countries like the United States and Canada are fully aware of.

On December 6, 1989, for example, a man named Marc Lépine entered the École Polytechnique de Montréal in Quebec. He went into a mechanical engineering class and divide the room by gender. He ordered the women to stand on one side while telling the men to leave. Then, after claiming the he was fighting feminism, he aimed an automatic rifle at them and fired.

At the end of that day, 14 women were killed throughout the school and 14 others were injured. Lépine also died; he killed himself at the end of his rampage.

It was one of the bloodiest cases of mass shooting Canada had ever known. And to understand why it happened, people needed to first understand the man who did it.

From Misogynist to Mass Murderer

Like a lot of people who committed massive crimes, the man born Gamil Rodrigue Liass Gharbi, Lépine had a troubled childhood. His father, Rachid Liass Gharbi was an Algerian immigrant and a mutual funds salesman who had old world, patriarchal leanings. He looked down on women, believed that they were only meant to serve men, engaged in infidelities and was both verbally and physically abusive to his family. Lépine’s mother, meanwhile was Monique. She was a Canadian nurse who was often at the receiving end of Rachid’s violence. Reports claim that he used to treat her like a secretary and that he’d physically assault her whenever she made mistakes.

The two separated eventually. And, after they did, Lépine and his younger sister Nadia were forced to live in other people’s homes while their mother returned to her work as a nurse to provide for their family. Rachid, meanwhile, was never seen again.

But do fathers like him completely disappear from their children’s lives or do parts of them stick around? Psychotherapist Previn Karian believes the latter is possible.

In an interview with In These Times (ITT,) a platform the focuses on mental health, he said that a person’s childhood tends to shape who they are as adults.

“The way a boy and a young infant learns to love women will be twofold,” he said. “First of all—and the primary one—will be the relationship of the father or other men towards his mother.” Sharing the belief of other psychotherapists, Karian said that when boys grow up seeing men respect his mother and treating her with civility, he will model himself after that. “But then,” he asked, “where are the fathers who do that?”

Not in Lépine’s childhood if all reports about it are accurate. Instead, he had a man who looked down on women, and he grew up being the same way.

A look into Lépine’s adult life revealed that suffered from loneliness, isolation and frustration because of his relationship towards women. He was interested in having a girlfriend, but he never managed to successfully woo anyone because of how bossy he could be towards women. He also harbored sexist beliefs reminiscent of the ones his father held. For instance, the idea that women should not be working; he professed the belief that they should instead be at home caring for their families (something his mother wasn’t able to constantly do because she had to work.)

Over the years, he started developing hatred towards the women who went against his belief. Chief among them were the feminists who fought for equal opportunities for women outside the household. He also began to hate career women and women in professions normally occupied by men.

In Polytechnique—a school that he wanted to study in—there were women who hoping to be in a field which Lépine thought was meant only for men. This was engineering, the course he wanted to take.

He never got in Polytechnique but it wasn’t because women took his spot. He simply lacked the compulsory courses which he was advised to take but never did. Still, he disliked the idea of women being there, occupying a space he wanted to be in.

So, one afternoon, he walked through the doors of that school with the intention of not letting some of them go out.

“Fighting Feminism,” Fueling Feminists

When Lépine’s killed 14 women to “fight feminism,” he ironically made it more aggressive. Champions of the women’s rights movement in Canada were shocked into immediate action. They saw the massacre as an opportunity to highlight gender-based violence in country.

The attack had a sweeping effect on local policies as well. For starters, it led to tighter gun laws leading to a ban on military grade, assault type weapons. Meanwhile, a House of Commons Sub-Committee on the Status of Women was created eventually releasing a report entitled “The War against Women.” Recommendations in this report were followed by the federal government which established the Canadian Panel on Violence Against Women.

In 1991, the Canadian government also established December 6—the day of the massacre—as The National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women. In accordance to the spirit of this day, Canadians established memorials in the country to remind people of the incident that occurred and urge others to recognize the dangers women tend to face.

Furthermore, the families of the victims mobilized. Some of them helped fund measures seeking to end gender-based violence. And On December 6, 1995, the government of Quebec adopted the “Policy on Intervention in Conjugal Violence” in an attempt to detect, prevent and end domestic violence which often victimize women.

This is a common occurrence in the face of misogyny that is too blatant to ignore. Citizens familiar with the instance of misogyny tend to rally around the woman or women affected by it and clamor for change.

Dr. Louks certainly felt that when many came to her side at the wake of the harassment she received. As of the writing of this article, the post which led to all of her recent drama had over 119 million views, 250 thousand likes, and 21 thousand shares. Meanwhile, the University of Cambridge–while penning its support for Dr. Louks–mentioned that interest for her controversial thesis has skyrocketed.

In other words, a lot of things tend to be done in reaction to misogyny but according to Karian, and other mental health experts, they are not enough. And the events that occurred in recent years backs this opinion.

In 2019, about 30 years after Polytechnique happened, the Guardian looked back at the attack and penned a grim opinion that “the massacre at Montreal’s Polytechnique school, fueled by misogyny, is not a horrifying memory confined to a bygone era – rather it seems like a foretelling of things to come.” And things did “come” according to the report.

The publication made mention of a woman in Chicago killed by a man after she ignored his catcalls, an incident in November that year when a man who exhibited hatred for women online open fired at a yoga studio, killing two women. Then there was another one again in Canada. On April 23, 2018, Alek Minassian, a sexually frustrated man, self-described as an involuntary celibate (incel,) drove a van on to a Toronto sidewalk killing 10 people. Eight of the victims were women.

After his arrest, Minassian said that his attack was motivated by the desire to seek retribution against women. He admitted to being part of an incel group which he got into after a friend from Seneca College directed him to an online messaging board meant for sexually frustrated men. He said he was inspired to act by those who were part of the group and have used violence to get justice for their inability to “get laid.” These include Elliott Rodger, the English-American mass murderer, another self-identified incel, whose frustrations led him to kill six people and injure fourteen others in Isla Vista, California on May 23, 2014.

Minassian said he was radicalized around the time Rodger’s conducted his attack. He hoped that his own rampage would inspire others to rise against the feminist movement.

“It’s unbelievable, isn’t it?” Karian said when his ITT talk ventured into a discussion about the incel movement.

Feminism exists because of the need to win women away from setups that have them treated like property or second-class citizens with very little autonomy. The idea that men go against this and complain that they are unwanted by women had Karian’s brows curling.

“It doesn’t occur to these people that men are the problem,” he said.

Can women contribute to it? Sure, he declared. He pointed out that some women choose to just accept the mistreatment they get from men and this enables the cultures that lead to their oppression. “They think it’s the norm,” he said. “They think it’s okay to be put down, shouted at, abused, made to give birth to children and work while, you know, the father or the other male partner does nothing.”

But there are many women that simply don’t accept this anymore.

“Of course, people now in modern society are realizing that we’ve got to move on from this,” Karian said. “Why? Because women are seen as equal human beings to men. And that strikes terror at the heart of men.”

Because of feminism and other movements that empowered women and gave them the right to make choices that determine their own fates, men are technically being stripped of outdated privileges. They used to decide how women should go about their lives. But this is no longer the case in many parts of the world. And Karian thinks this is partly the reason why many are lashing out—sometimes in ways that end lives.

But based on existing evidence, going back to the way things were won’t make it things better. In “Misogyny: The Male Malady,” a book written by anthropologist David D. Gilmore, evidences of misogyny are found to have existed long before the fight for women’s rights started causing meaningful change. It is in customs meant to diminish women, in mythologies that normally write women off as the source of all of men’s problems and it is in practices that risk their lives—from gender mutilation, to forced marriages, to witch hunts. It was a problem even before it had a name and it stuck around even as human civilizations expanded further and branched out to various iterations.

“Everywhere we look,” Gilmore wrote, “men are sorely divided in their feelings toward women, but everywhere the repetitive emotional complex in so many males clearly points to some psychogenic factor above and beyond the vicissitudes of social context or environment.”

He then added that explanations for misogyny based on politics or economic systems “cannot do complete justice to the problem,” because based on his research and the works of others who looked into the subject, “all political systems, economic arrangements, and ideological systems are consistent with misogyny.”

“Woman-hating,” he wrote, “is just as bad under capitalism as it is under any of the various socialisms or under tribal communalism; misogyny occurs in ‘prestige’ economies without money just as virulently as in modern cash-oriented economies.”

The only way to address it then is to move forward and according to Karian, that could start by identifying misogyny for what he, Gilmore and many mental health experts believe it to be: a mental health problem.

“When you strip away all the machismo of the male persona,” Karian said, “when you strip away all this bravado and posturing that men do, they are very scared brains inside the male skull and this is something that needs to be understood without trying to shame men by the way. This is not an occasion to simply attack men. What we need to do is try and ask ourselves where is the problem of misogyny located and it is clearly not in the law, it is clearly not in culture, it is somewhere in the human brain.”

As a man, Karian attests to this. In his interview, he admitted that he too can have aggressive thoughts that can—when left unchecked—harm women. But they never manifested. He thanks his background in psychology, his ability to process his thoughts and pinpoint where the real problem is as far as he is concerned. And more often than not, the problem, he said, was coming from him. Not women.

Some men, he said, don’t do that. Some would rather see women as the primary reason for their pain and we live in an age when many men who think the same way can validate that.

This was pointed out in the Guardian article looking back at the Polytechnique massacre. Julie Lalonde, a Canadian educator focused on violence against women said that there is a link between Minassian and Lépine its quite “clear,” “direct” and “obvious.” Both men were sexually frustrated, and angry over the lack of affection they thought they were owed.

There is a crucial difference, however. Lépine’s attack happened in 1989—in the days when most research is done through printed materials, word of mouth and time-gated, mostly filtered content (like that which can come from television or radio.) Information transfer was much slower during his time and in the Guardian article it was mentioned that it took him around seven years to build his extremist views. Minassian attacked in 2018. If he was being honest when he said that he got radicalized around the time Rodgers struck, then it only took him four years to be driven into violence.

In other words, Minassian was radicalized much quicker thanks to the internet—this global system where people can easily share what they do, who they are and what they believe and quickly find people who want to support it or tear it down.